In Conversation with Eloisa Guanlao

Cover image: Eloisa Guanlao. Holo Mai Pele (2017), bamboo and piña cloth, 200 x 200 x 144 in. Allys Palladino-Craig.

“The circuitous journey that produces an object—from the minefields to the factory floor—both fascinates and repels me.”

Recently, I had the pleasure of interviewing artist and scholar, Eloisa Guanlao. Born in the Philippines, Guanlao is currently a faculty member in the School of Arts at California State University, San Marcos. Eloisa’s broad interests in the natural world, history, dance, art, and literature is cultivated by an intensive research-based process and informed by her own nomadic experiences as an immigrant, artist, and scholar. Having exhibited internationally, she recently participated in Future Perfect, a group exhibition on climate change awareness at Durden and Ray gallery in Los Angeles, which I curated on behalf of MPAC.

In this interview, Guanlao shares the longstanding influences on her research-based process, her inquiries into the cultural history of technology as it intersects with colonial rule and processes of racialization, and the ramifications of the current political shifts on marginalized communities in the United States. Included in this interview are reflections on the role of artists and the impact of the arts for social change.

Vuslat D. Katsanis: Your work is set on the intersection of history, technology, and identity through an intensive research-based approach. Can you say more about your process through some specific projects? What are your influences?

Eloisa Guanlao: Three themes interweave within the fabric of my labors in art: migration, colonialism, and technological dependence. L’exposition Universelle (2005) and Re-framing Progress: Science, Art, and Empire (2007) comprise all three.

The conception for both projects stemmed from my readings and writings on the U.S. antebellum period, comparative colonialisms (British and Spanish), world’s fairs and human zoos, nineteenth-century photography, and the development of modern art vis-à-vis European colonial exploits and looting. Barbara Jeanne Fields’ essay on the formation of American racial ideology in “Slavery, Race, and Ideology in the United States of America” (1990), Stephen J. Gould’s scrutiny of scientific racism in The Mismeasure of Man (1981), and Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1935) heavily influenced these works.

L’exposition Universelle examines the myth of objective truth tied to photographic technology. Early photography claimed to reveal a person’s true self due to the machine objectivity ascribed to cameras. Photography was used to develop early mugshots, stereotype individuals, and naturalize a so-called hierarchy of races, placing Europeans at the top to justify oppression, colonization, and forced servitude. I created long-exposure, large-scale stereoscopic tintypes of myself dressed in Hawaiian regalia as one of modern art history’s exoticized female subjects: Picasso’s demoiselles and Gauguin’s Tahitian women. These tintypes were placed in a stylized large wooden camera to simulate the act of seeing, capturing, being seen, and being captured within a specific socio-cultural time and space. World’s fairs showcased European technological progress while simultaneously displaying oppressed colonial subjects in human zoos.

Similarly, Re-framing Progress overturns the white supremacist narrative of Manifest Destiny and progress. It reflects on icons of transportation technology, from wooden outrigger canoes to steam locomotives, emphasizing the impact of westward expansion during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It recognizes the participation and resistance of individuals, including Chinese immigrants, African Americans, Native Americans, and European Americans. As an architectural site of memory, it invites the public to reflect on its role in the ongoing evolution of technology and development. The activity at diverse transportation hubs, such as Los Angeles Union Station or Albuquerque Airport, where Re-framing Progress was installed, is mirrored in the reflective holograms and tintype images that compose the structure’s walls. The form I chose amalgamates architectural styles common to grand central stations built in the U.S. and Europe during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

VDK: And how would you describe your choice of materials or medium for your process?

EG: The circuitous journey that produces an object—from the minefields to the factory floor—both fascinates and repels me. This journey of material culture informs my art practice and the mediums I use. When an issue nags at me and an idea forms, I ask: Am I the right person to address this issue ethically? What is the proper material? What is the material’s relationship to the idea? Does the material easily break down and lack archival qualities? What meaning is already imbued in the material, and what new meaning am I trying to infuse through its reconstitution and arrangement?

In terms of material choice, Mary Kelly’s “dirty nappies”1 inspired me to use my daughters’ outgrown clothes to sew the hundreds of birds that make up Aves in Darwin’s Finches (2016–2024). These clothes are relics of family hiking and camping excursions, during which natural history is observed or collected in the form of discovered fossils, feathers, flora, or deteriorated animal bones and carcasses. As both an artist and a mother, I challenged myself to involve my daughters in my work, and the durability of the “stuffed” birds aligned perfectly with my toddlers’ play.

My favorite medium is dance. As we increasingly inhabit separate, passive virtual spaces, I deeply appreciate the physicality of dance and the limitations of my aging body. I dance in a hālau, which for me is the perfect fusion of art and life. A hālau is a Hawaiian word that literally means “a branch from which many leaves grow,” but colloquially refers to a hula school or group. Hā means breath and lau means many. Dancing in a group, we breathe as one. It combines music, physical exertion, visual presentation, ephemerality, the preservation of a minority language and tradition, and communal cooperation.

VDK: Throughout your body of work, there is a clear critique of the unregulated expansion of technology especially as it impacts vulnerable communities, and an interest in telling the stories of human labor and migration. Could you talk about a specific project or two that speaks to your interest in institutional systems and their effects on communities?

EG: When I look at technological expansion and our dependence upon it, I contextualize all forms of technology through time and space, from the rudimentary to the digital—such as outrigger canoes for the ancient Polynesians or guns for the Spanish conquistadors. I study the role technology plays in the ecology of a place and the makeup of a society. The technology of writing on clay tablets and the printing press allowed us to control large empires through impenetrable bureaucracy. Digital information technology at our fingertips now sways our very worldview and daily reactions. Polynesian settlement in New Zealand caused the extinction of its megafauna. Railroad technology allowed the rapid settlement of western lands in the U.S. and drew cheap laborers from China. Uranium mining caused a high level of cancer among the Diné in the Southwest, and its development eventually paved the way for the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Starlink gives Elon Musk control over whether Ukraine or Russia has access to troop formations. Using a smartphone or computer signifies personal dependence with dire implications, as they are made with precious metals mined in places such as the Democratic Republic of Congo or China, where forced evictions at mine sites, deplorable working conditions, and human rights abuses are prevalent. The Anthropocene is ripe with stories of how we jump all too readily on the technological bandwagon without much circumspection.

The Anthropocene is ripe with stories of how we jump all too readily on the technological bandwagon without much circumspection.

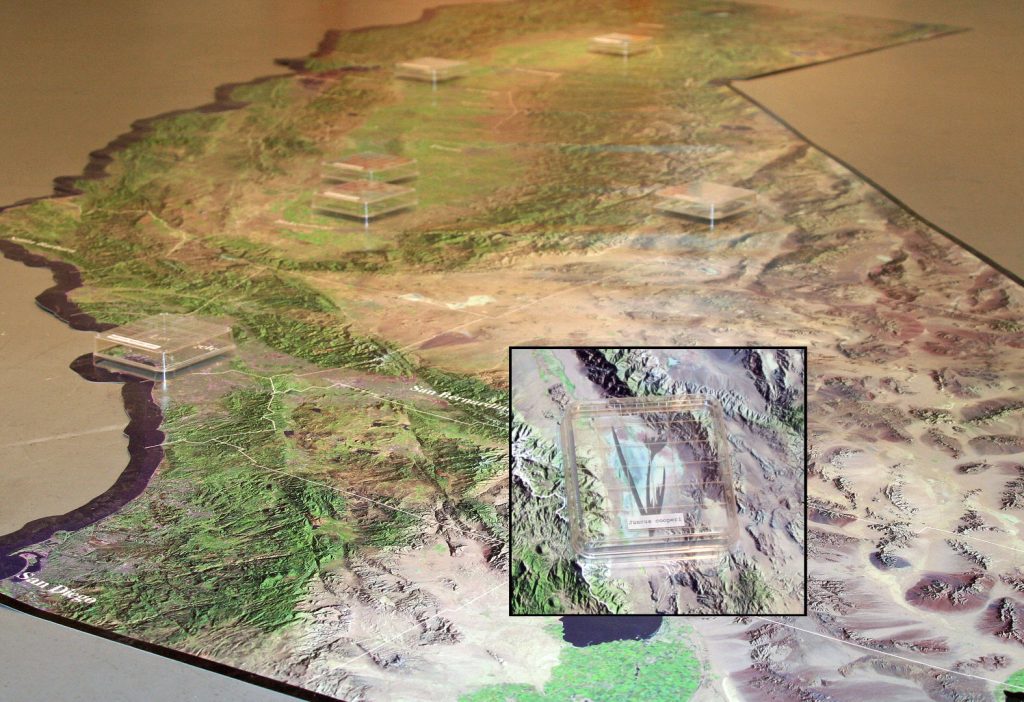

Holo Mai Pele (2017) recounts the Hawaiian deity Pele’s unrelenting search for a home. Her difficult story of migration and fraught encounters is replayed with changing casts of characters through different times and places, such as in the occupation of the Solomon Islands and Marshall Islands during the first and second imperial world wars of the twentieth century or the colonization of the Philippines from the fifteenth to the twentieth century. Holo Mai Pele provides a stage-like platform where Pele’s journey becomes an allegory for the legacy of colonialist domination that persists to this day with catastrophic outcomes—the loss of a way of life and home for island dwellers due to rising sea levels. Pele’s voyage is the launching vehicle for Talking Story, a series of installations and documentary performances that examine and question the historical archives of human migration, territorial expansion, and natural resource extraction across four continents over five centuries, all entreating for environmental justice. The series seeks to counter the disparity and community disruption that arise as groups cling to or gain access to prime land and resources. Environmental justice resists the us-versus-them colonialist mentality that regards the earth as real estate to possess, carve, and subjugate.

Holo Mai Pele considers the privileged North American position vis-à-vis unchecked climate change, whether as passive bystanders or engaged participants. I appropriate the material cultural form of the map as a signifier of colonialist domination. Mapping denotes ownership, a sweeping administrative overview of dominion and resources. The surfboard-sized oars contain two maps. On one side is a colonial-era map of disappeared or disappearing lakes, and on the other side is a present-day topographic low-relief map of disappeared or disappearing islands.

I appropriate the material cultural form of the map as a signifier of colonialist domination. Mapping denotes ownership, a sweeping administrative overview of dominion and resources.

VDK: Have you found yourself drawing upon personal experiences as you explore these histories, or vice versa?

EG: The factors and circumstances that have affected my own immediate family and our place in the world can be traced to Spanish colonial Catholicism and overseas employment. The Catholic Church, as the spiritual arm of the Spanish colonial sword and coffers, remains the preeminent institutional system in the Philippines, influencing social norms, values, and sexual mores. Its infusion into the spiritual life of Filipinos facilitated Spanish colonial rule. Just as prevalent, a notable portion of the Philippines’ GDP comes from the remittances sent home by OFWs (overseas Filipino workers).

Noli Me Tangere (2017–Present) is a two-part project that takes place in the environs of Manila. The first segment is an installation-interaction consisting of a life-sized, cast paper jeepney covered with comic book pages designed by my father—traces of childhood memories of my father’s creativity and hard work left behind for better prospects abroad. It is mounted on a wheeled bamboo raft, referencing vivid childhood recollections of intense annual typhoon flooding. The second component is a personal documentary film that examines forced and voluntary human migration as a legacy of colonization through my own family’s story of transplantation, following a larger historical progression of human capital flight from the Philippines.

The cast jeepney serves as the vehicle for drawing people into valuable conversations about history, society, and culture’s relationship to colonization and migration. Acting as a traveling comic book stand, it beckons local passersby to read its pages. The comic pages contain enduring tales of losing loved ones to immigration, reflecting their own lives. Filipinos are all too familiar with immigration’s sacrifices and benefits, and most are touched by it in some form or another. A staggering ten percent of the Philippine GDP comes from remittances sent from abroad. I ask willing passersby to write the names of their family members abroad inside the jeepney and record their stories on film. The jeepney, a World War II American relic appropriated for popular public transportation, is a colorful and flashy banner of Filipino identity, often graced by the protective figure of the Virgin Mother on the dashboard—herself an icon of Spanish colonial domination. As such, the jeepney is an ideal symbol to foster dialogue, precisely because it cuts through sensitive and central themes of colonization, transportation, migration, and identity.

The cast jeepney serves as the vehicle for drawing people into valuable conversations about history, society, and culture’s relationship to colonization and migration. Acting as a traveling comic book stand, it beckons local passersby to read its pages. (…) As such, the jeepney is an ideal symbol to foster dialogue, precisely because it cuts through sensitive and central themes of colonization, transportation, migration, and identity.

The Noli Me Tangere documentary traces the life of my father, from his early days as a comic book artist in the Philippines to our family’s resettlement in the United States, vis-à-vis the larger issue of Filipino emigration. I visited comic book publishers for whom my father worked in Manila and conducted interviews with family members, as well as my father’s friends and colleagues. The project seeks to understand the motivations and consequences of Filipinos choosing either to remain and contribute to the cultural and socio-economic development of their birthplace, or to seek their fortunes elsewhere.

Free Water (2013) is another project that examines and maps an actual system of distribution—in this case, water. I conducted a series of interventions at multiple business districts and work sites in Los Angeles and San Pedro. Alongside other food trucks and vendors, I parked the “Free Water” truck, advertising fresh water for free. When someone asked me for their free water, I gave them a field guide containing a map with directions to the water sources for the Los Angeles basin. The field guide included the following questions: Would you be willing to move somewhere where water is readily available? How much physical work are you willing to exert to collect water manually? Which of your daily activities consume the most water? How much comfort are you willing to give up to obtain this water? Is water in southern California really free?

Eloisa Guanlao. Images 1 and 2. Free Water (2013), Inkjet Print, Acrylic, Wood; Water Truck: 60″ x 90″, California Map: 48 x 96. Courtesy of the artist.

The final exhibition combined a large-scale floor map charting the water sources and distribution networks for Los Angeles, along with the tabulated responses from “Free Water” truck customers. The map included the various fauna, flora and human communities impacted by the technological infrastructures that make water available to Los Angeles. The viewer could trace both the water and my journey physically and metaphorically by walking on top of the map.

Balancing, combining or separating, and reconciling art and activism are integral to my art practice. I am wary of exploiting an issue into an empty spectacle for art’s sake. Sometimes art need not be involved; the simple tactic of going door to door to persuade someone regarding an issue is enough.

VDK: Your practice of researching, archiving, and retelling also questions who benefits and who suffers under institutional systems. When I look at your works, such as “Variation” from the series, “Darwin’s Finches,” I can sense a somber contemplation. Yet, there’s also an aspect of looking forward. How do you balance addressing these inequities while fostering hope through your art?

EG: I am humbled and delighted when individuals come up to me and tell me how they appreciate my artwork or have been affected by it, but it often falls short of my socio-political aspirations for an environmentally responsible and equitable society. I find myself unsatisfied with these little increments. Balancing, combining or separating, and reconciling art and activism are integral to my art practice. I am wary of exploiting an issue into an empty spectacle for art’s sake. Sometimes art need not be involved; the simple tactic of going door to door to persuade someone regarding an issue is enough.

My installations mirror their protracted process of production. They require a lengthy amount of time and energy to actualize. Installations are solemn spaces of reflection, internal conflict, and study, with discrete parts contributing to a larger narrative. Ultimately, though, they are a way for me to make connections with others.

Science fiction writing by Black female-identifying writers like Octavia Butler and N.K. Jemison offers me hope and some comfort. Their world-building shows possible counter-narratives as bulwarks against the limitations of our current myths regarding political, social, and economic structures. The boundless dimensions of biological evolution are likewise a source of hope, learning, wonder, and humility for me. That evolution occurs incessantly, incrementally, and with infinite possibilities takes me out of spiraling into self-pity and cynicism and reminds me that change is part of existence.

VDK: On the note of worldbuilding, the concept of reclaiming subjective space for socio-political interaction is central to your work. How do you envision these spaces involving audience participation? I imagine that the scale of your work, the location of display, and other experiential decisions have an impact.

EG: The phenomenology of Robert Morris’ Untitled L-Beams (1965), Hans Haacke’s criticism of German racism in Der Bevölkerung (2000), and Adrian Piper’s Calling Card (1986) are works that opened the possibilities of the “expanded field”2 of public space and audience involvement. In my installations, such as Darwin’s Finches, and architectonic works, such as Holo Mai Pele, the aim is to build a physical stage where one, through interaction with the work, becomes self-aware, takes notice, and, hopefully, delves deeper into lengthy introspection and research.

Voyage In… Voyage Out (2004-2006) is a series of three oceanic canoe-inspired vessels, each intertwining stories that connect diverse people and places. I wanted to share Polynesian and Filipino oceanic cultural heritage to the desert. The first canoe explores a cosmic dance of myth and survival, blending celestial constellations, fighter jets, American jeepneys, Filipino traditional dances, and principles of physics. The second canoe represents the dreams and aspirations of youth from surrounding New Mexico communities. The third, adapted to the dry terrain of the western United States, grows wheels and travels to various communities in New Mexico and southern California, where I facilitated photography, performance, and video workshops focused on oceanic traditions.

This project is deeply mindful of the cultural appropriation and artifact theft experienced by New Mexico’s Pueblo communities. The canoes remain my most successful project in fostering a cross-cultural initiative that would respect and honor these traditions without exploiting the Pueblo people or their heritage. Creating these vessels was a rewarding experience for me and also for the Pueblo youth, who brought new perspectives and energy to the project. Through Voyage In… Voyage Out, I found a meaningful way to engage with communities while honoring cultural integrity, and fostering a sense of shared storytelling across different backgrounds.

VDK: What’s next for you? We would love to hear about any upcoming projects or ideas you are currently exploring.

EG: I am still collecting footage for the documentary that I am making on my father and his fellow komikeros, as well as spending time in the darkroom printing images that I shot with infrared film in the Smoky Mountains and the Denver Botanic Gardens. Even though I was anticipating Trump’s win, I was nonetheless bitterly disappointed and demoralized by it and the electorate that made it happen. My ongoing projects will have to simmer on the back burner because the next four years will need to be devoted to counter-programming a society that is veering right, a culture that idolizes strongmen, and a court system that demeans and strips rights away from women and the LGBTQIA+ community. Conversations with thoughtful friends and colleagues involve exploring the most effective long-term strategies and short-term tactics in the struggle for human and civil rights and environmental sustainability, whether it involves art or not. Mutual aid groups, podcasts, AM radio content, and short-form videos on digital platforms are some possibilities, but collaborative work is necessary to keep morale and spirits balanced.

My ongoing projects will have to simmer on the back burner because the next four years will need to be devoted to counter-programming a society that is veering right, a culture that idolizes strongmen, and a court system that demeans and strips rights away from women and the LGBTQIA+ community.

Artist Biography

Eloisa Guanlao, born in the Philippines, draws inspiration from her immigrant journey and life as an artist, scholar, teacher, spouse and mother. Her versatile art practice reflects her deep interest in nature, history, art, languages, and literature—passions sparked in her youth and nurtured through diverse educational experiences. She honed her craft at the Los Angeles High School for the Arts, pursued liberal arts studies at Carleton College, and earned an MFA in Studio Art from the University of New Mexico. Believing art to be a social and cultural endeavor, Eloisa engages in research-intensive projects addressing contemporary issues. Now rooted in California, Eloisa continues to practice and teach art, fostering creativity and critical inquiry.

- Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, 1973-1979. ↩︎

- Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” in October Vol. 8, Spring, 1979. ↩︎