MPAC in Conversation with Lauren Alyssa Bierly

Ilknur Demirkoparan

We are sitting here with Lauren Alyssa Bierly, one of the three artists exhibited in Enduring Time | Material Emergence.

Lauren, thank you for joining us. It’s an honor. Would you start by giving us an introduction to who you are and how you started your practice?

Lauren Alyssa Bierly

Yes, thank you for inviting me. I am an interdisciplinary artist, and also consider myself a researcher. My artwork is rooted in phenomenology and informed by architecture, ecology, and language. I started my practice in 2012. I wasn’t trained as a visual artist through my undergraduate career, I was trained in architecture. I attended architecture school for five years in central Pennsylvania, then moved to New York City to attend grad school for modern and contemporary art history. I started in the arts from a project and exhibition management standpoint, before beginning my art practice after working with artists in the residency that we were running at my first full-time gig at the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts’ Project Space.

My practice is separated into two series: my Architecture of Memory series, and my Color Translation series. Color Translations is the project that launched my practice. I have synesthesia, which in layperson’s terms, is a crossing of the senses. The most common version is grapheme-color synesthesia, which is when you see letters and numbers in color. Some people hear music as color, which is commonly attributed to artists like Kandinsky, for example, or contemporary musicians including Lady Gaga and Pharrell Williams. So I was really interested in seeing how I could look inward and translate this sensory perception into a physical form.

I spent the first couple years of my art practice developing these three-dimensional installations that translate my experience with synesthesia into a physical form. I work with acrylic paint on plexi because these materials really speak to the vibrant, ephemeral and sometimes plastic experience of what happens when I read letters and numbers in English. As I was developing that project over time, I also was finding myself taking long walks through the city, to become more familiar with this new urban environment that I was now living within. I noticed how my perception, similar to that of synesthesia, was affected within different spaces. For instance, taking note of sensory cues going from the city street to being within my apartment, to being in a park within the city, or going back to Pennsylvania to visit the countryside is something that became much more heightened for me all of a sudden. This is when I started this other branch of my practice, Architecture of Memory. Architecture of Memory looks more deeply into the languages within an environment and how they affect our behaviors through individual, different perceptions. That project has grown significantly over the years. The first time I developed a framework for this series was in New Mexico, again, when I was in a different environment. And through these changes from environment to environment, I was noticing more and more things that I wanted to document through photo, video, or specimen collection, and then turn those inward perceptions into a physical manifestation.

Vuslat D. Katsanis

This is really fascinating to hear you describe these branches of influence. I’m coming from an angle of literary arts and studies. Hearing you describe your practice and your understanding of the sensory environment as a language, and what you do with that language as translation, is really fascinating. As someone who’s also doing literary translations, that’s definitely something that I am interested in both as a metaphor, but also in terms of a practice. Translation requires close proximity on the verge of intimacy with what is outside of yourself. It almost necessitates an ethics of deep listening and leaning in to really hear what is inside somebody else’s work. And through that process, someone else’s inside ends up becoming an extension of yourself, requiring a certain ethics of exchange.

I see a similar intimacy between your work in Enduring Time | Material Emergence and the viewers. Your work kind of unassumingly but intentionally and humbly takes up a large space on the wall. And its humble but unavoidable presence is what invites close exchange.

Ilknur

And you have to slow down too. It’s almost like the artwork will offer you things. Since I’m the one who’s gallery sitting all the time, I get to see how people interact with your work. I recall these two women who walked in and began looking at it, then their body shifted a bit, and they realized that this is something you need to spend some time with, to get up real close. And because it’s so quiet in the gallery, the work feels almost like a whisper. So, I watched them lean a little closer and closer, very slowly inch toward it, almost as if holding their breath. It’s such a delicate material too with pencil on paper, which means you could accidentally smudge it if you’re not very careful. So vulnerable.

Lauren

That’s so good to hear! I just love hearing this and also both of your interpretations of the work; the feedback and the conversations with visitors, too, because this grid of drawings itself may not immediately pull you in, which is intentional. One thing in architecture school that was really pounded into us was line weight and hand drafting–essentially the basic skills like foreground, middle ground and background–and really making visually translatable technical drawings of buildings and whatnot. I struggled a little bit when I was preparing the drawing before I sent it out to you all, because part of me was unsure if I wanted certain layers to stand out from others, or if I wanted it all to be uniformly quiet. The drawings were done so quickly in the moment–[documenting in the studio as the morning sun moved across the studio wall]–so the magic is really in the viewer’s discovery of the numbers on the pages identifying which layer is which. It invites you to come in close to see each layer, and you have to connect the dots.

Vuslat

And if I may, go back to this idea of the sensory environment as a language that you translate. Can you say a little bit more about why language rather than another thing, and why the numbers? I’m here thinking about linguistic rules, for example. You also mentioned the word “document,” as in documenting time. Curious to hear more.

Lauren

Yes, definitely. From a young age, I remember wondering if there was a universal language and how we, as people, started to communicate with each other. If there is a universal language, what could that be? It’s something that I was interested in studying, either through the philosophy of different concepts like beauty or color theory, or in psychology. I am still really interested in this universal language that gets to the core of what it means for us to be human– obviously not a spoken language and not a written language. What is this other universal language based on our feelings more than anything else? And what triggers those feelings? And so you start to think about things like where you feel comfortable, where you feel uncomfortable, how your body reacts within certain situations in terms of sweating or like the hair on the back of your neck standing up, or whatever it might be. All of these are sensations, sensory driven moments. And it’s all something that we experience. We have a different word for these things in every language, but it’s something that as humans we share. What has become more interesting in especially the last couple years or so, is seeing how that same sensory input and output translates to the natural world. I like to believe that there is a universal language amongst all of us whether you want to call that an energy, or a sensory output or whatever that might be. That’s kind of where that all comes from.

Ilknur

This reminds me of a conversation that I was very fortunate to be a part of years ago as a young undergrad. We had a master class with visiting artists Karl Berger and Ingrid Sertso, jazz musicians, invited to our campus. The word got out that they were in town, and a magazine wanted to take them out for dinner for an interview. And, you know, being a young bright eyed kid, they allowed me to come along. I remember they were having this conversation about what it is to be a human and what it means to express. Ingrid Sertso said, if you ask people who sing, they will tell you that the first ever creative expression was likely a cry. Karl Berger said well, if you ask a percussionist, they will tell you that it was probably a strike, maybe something out of anger, frustration, or even joy. And I remember just sitting there knowing full well that I shouldn’t disrupt their interview, but something came over me, and I blurted out that may be it was scratching away at something! But you know, why not all of those things, right? Why not all of those at once? Which was really the point Karl and Ingrid were making.

Lauren

Yes, exactly. We have many ways to communicate with each other, all starting from instinct, which is sensory. And so I like to think, especially when I’m in the studio with this particular series [Architecture of Memory], that it’s literally an uncovering of the building blocks that make up our senses. Just like a sentence is structured, each letter makes up a word, each word sequenced together makes up a sentence, sentences make paragraphs, and so on. All of this could be similar to the building up of these blocks into a sensory output or a sensory exchange. The framework of sensory output can then be translated into a metaphor for things like an architecture or translating, you know, a text, or writing a song. It seems to be just the core element of everything that stands together, and music is one of those universal languages.

Vuslat

One thing that I hear in what you’re describing, and also from my experience in the gallery with your work is that it involves the body. Speaking of the human element and that universal language, there’s also a sort of a computational element. We are navigating this world, this grid, where we’re constantly translating, coding, and decoding. So the process is computational, mechanical, and at the same time, deeply organic, fleshy, and human. Those two things in this case aren’t contradictory. You mentioned the sweat on the back of the neck as an example. So what I thought about with your artwork is that it’s pencil on paper traced delicately with an unassuming presence, like skin. Skin is this intimate organ we all wear on the outside of our bodies as the surface we interact with. So there seems to be a sort of bodily choreography as another kind of exchange, with people leaning in, kneeling down, turning to the side to get another view. At the end it all comes to what you feel in and through your body.

Lauren

Yes, exactly. And that’s why it’s so nice to hear what you’re experiencing with it being in the gallery and people who have visited: slowing down and actually taking time with it, leaning in and standing back and following the different parts, each page of the grid of drawings. The intention is to slow down and connect to what you’re looking at and how it requires you the viewer to move.

I have this Instagram account that I’ve started called mind.s.pace, and it’s a new iteration of the Color Translation series that I’m doing, except this time digital. I started this in the pandemic with my partner’s encouragement, also because it felt simple and easy to do at the time. I choose a word or phrase and then I translate that word into the colors I associate with each letter [based on my grapheme-color synesthesia]. I then reflect on what that word means to me in journal entry form. I was recently writing about “mind and body” for this project, the combination and balance of mind and body, and what that means to me and my practice. My practice really is about making that connection between the mind and body. Very often we’re either stuck in our minds, or we’re moving our bodies, but when do the two of those come together? So it’s nice to hear the interaction with the piece because that’s essentially the two coming together. That’s the connection that I’m hoping for.

Ilknur

It’s almost insane to think about interaction, post-pandemic, though we haven’t cleared the pandemic yet with new variants of the virus emerging. But you have to think about that human connection now, more than ever. We have been so deprived of it for the past year, it puts into perspective what we take for granted every day. And it makes you really rethink what you described earlier about navigating the world as a human. It’s not just things that are material that you interact with: you pass through light, a shadow falls on you, you navigate through the dark, you navigate through cold or a heatwave. It’s like everything else that we are made to think about in this world is sheer bullshit, where you kind of cut all of that out and put yourself out there in its bare human form. And then you really think about who we are and what we are doing and that’s when we really connect.

Going back to your choice of paper, and how it’s like skin, so delicate and vulnerable just hanging on the wall with those two pins on the top corner — it’s so poetic! Initially, I wanted to hang them on the opposite wall. But I realized that because we have a skylight in the gallery, the afternoon light, when the gallery is open, falls on this wall. So I realized, it needs to be on this wall because these were done in Oregon. They record a certain time in space with this human who was there and her work is now in Oregon again. The same sunlight is now sweeping over an earlier hand-traced record of itself. Then the air conditioner kicks in and the papers make this swaying motion because they’re hanging on two pins, at which point you’re just thinking, wow, I can feel her hand moving across the paper.

Lauren

When I was working on this grid of drawings in my studio at Playa Art + Science (Playa) in Oregon, which is in the high desert, the same thing happened. It was the dead of winter, the heater that was in the studio would kick on and the fan that ran would create enough of a current to move the paper as I was drawing on the pages, which made it super difficult at times to continue the gesture, the line, from one page to the next. It is great to hear that you have that air conditioning doing the same.

Vuslat

Last time we spoke about the theme of the exhibition, we talked a lot about endurance and resilience. And now I’m thinking, yes, but we’re not out of the pandemic yet. And even if we are, it is something that will have a profound effect on how we live the rest of our lives. There’s a kind of thing that we’ve endured, but that very thing is also enduring in the sense that it has left a permanent mark.

You said you did this piece during the lockdown when you were away from home and in a new environment. There was something frightening in those early days of lockdown–it was terrifying to see the whole world close borders, while we think “what if something happens and I cannot go to my home country when somebody needs me?” That kind of worry in my experience, closely resonates with an immigrant experience. Suddenly, finding yourself in a new space and in a new situation, to which you very quickly must adapt in order to survive… you’ve got to build your community, you’ve got to find those resources that sustain you. The only way to make it out alive is to make that space a home. So it resonates with the immigrant experience in the sense that the struggle becomes formative to your worldview. I think the pandemic sort of turned us all into immigrants, rethinking who we are and how we relate to one another through this new constraint.

Lauren

Yes, definitely. At the beginning of the pandemic before we really knew anything that was going on with COVID-19, I was in residency at Playa. Before I arrived, all of us received an email from the staff requesting that if you’re feeling ill please don’t come. Then we received a packet of information to prepare for the trip because the residency is very remote; at least an hour, maybe two, from all amenities. Any of the food, medication, or toiletries that you needed for the duration of the month you brought in with you. All the things that you would typically have such close access to on a daily basis, you’re now shifting yourself to thinking about planning for a full month and avoiding any sort of emergency. During the residency, a couple of us had an odd ailment, and we individually connected it to homesickness. I was having these dizzy episodes when I was actually creating the drawings on view in the exhibition. As a cohort, we’d rationalize “maybe it’s altitude change, or maybe it’s dehydration because we’re hiking in dry conditions,” but we kept coming back to this idea of our bodies subconsciously mourning whatever the earth was feeling at the time.

Vuslat

It’s interesting that you said homesickness. Going back to synesthesia, to this day if there’s a specific temperature in the air, or the intensity of the breeze as it hits my skin, it takes me to a very specific time in my childhood. Not even a special memory, just an ordinary time. Same with fragrances, there could be a very specific but ordinary smell, and it takes me somewhere.

Lauren

And that’s the reason for the title of this series Architecture of Memory; the memory that transports us to different times within our life. It’s all time-based and in our minds. I’ve read that taste and smell are two of the top factors for long-term memory recall. So all these internal structures over time build up perception in different ways in our minds. And often we have to ask whether memory is reliable. Our emotions are affected so much by those sensory absorptions depending on the conditions of the environment.

Vuslat

I wanted to also ask you about your experience with art management. You have this insight into how things happen behind the scenes. Do you mind sharing a little bit about that experience?

Lauren

I attended graduate school at Christie’s Education which is affiliated with the Auction House Christie’s here in New York. I chose that particular program because they emphasized the program would be very hands on with the art. They were focused on exploring the theory and philosophy of art over time, specifically from the 1900s through present day. Whereas some of the other programs I had looked at were more focused on the business aspect of art. The program was fantastic. After completing the coursework, we were required to intern with a cultural institution like the auction house, a museum, or commercial galleries. I wasn’t interested in those; I was more interested in the alternative nonprofit scene at the time, because the deep conversations happening with contemporary artists were more fascinating, more satisfying to me.

I secured an Exhibitions Internship with the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts’ Project Space. During my time at the Elizabeth Foundation, both as an intern and then as an employee for a little over five years, I met hundreds of contemporary artists and had really wonderful conversations about concept, process, material, installation, and experience. We also worked with independent curators who preferred to be present in the gallery in order to understand how the space would be laid out with artwork. What conversations were being had on the wall, in the space. There was this bodily element to curating that I really loved. I eventually left the Elizabeth Foundation and made my way to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute department. They had a position open for a Project Manager for the Costume Institute, someone who could basically translate scholarly research from the curator to the design and experiential portions of putting on an exhibition, and then track the processes that needed to happen within the curatorial department to get that done. Having experienced a couple of the Costume Institute shows in the past, I was really excited about this combination of art and architecture as I saw it.. Then over time with these two institutions and various others, I’ve been collecting all of these people skills, budgetary skills, time management skills, design skills, art and curatorial skills, the practical and the impractical, a little mix of everything.

This past January, I joined the Brooklyn Museum, which is where I’m currently working as an Exhibition Project Manager. Most artists don’t get to see behind the curtain of an exhibition, and I find it to be super helpful to the art practice I’m building. I’m again working with contemporary artists and helping them navigate the museum system in a way that [hopefully] benefits them the most; knowing well as an artist, what you need creatively and how to navigate that bureaucratic museum territory.

Vuslat

Thank you for sharing that. Since launching the postcollapse project and opening our physical project space as the MinEastry of Postcollapse Art and Culture, it’s just been the two of us. Yes, we have a relatively small space and we’re doing our own small thing, but it’s an incredible amount of work and incredible amount of labor on the part of everyone involved, including the artists. That’s why I was so interested in hearing from your experience because doing this on a larger scale with so many different people and departments, the sheer coordination and collaboration required, from probably grant writing to promotion and outreach to reviews to catalogs, and documentation– it’s an entire orchestra. We want to do as much as we can, between the two of us, but we’re also really invested in theorizing the very idea of collaboration: what does that truly mean and look like?

Lauren

Yes. And that’s why I’ve continued arts management, because of the collaborative element of putting on an exhibition. Collaboration really is a way of building community, it takes an army to put on a show. And, that’s something I’ve always really enjoyed– the critical dialogue around planning that brings people together. That’s why I think artist-run spaces are so fantastic. When Ilknur first told me that you both were opening a space I thought, “oh my gosh, it’s finally happening!” When I first talked to you back in the summer of 2019, the idea felt nascent but hungry to grow. This is exciting that you now have this space to actually manifest all the things that you were thinking about over this whole time.

Much of arts management is about taking risks and using your intuition; you feel this is the moment, like this feels right, you know, it’s a lot of gut reactions.

Ilknur

Yeah. Yeah, for sure, you just, sometimes you just got to do it, you know? You can always prepare a little bit more, like you need to do a little bit more until you are ready. But then there are times when you just feel ready. The postcollapse project began as a research project in December 2018 when we planned to write a book. Once we started the project, it started building more and more, putting together the different parts. We are still doing our research for writing that book, but we’re also interacting with a lot of artists, and why not have a space to show their work and learn from their practice? Then Vuslat proposed that we publish our conversations with the artists and capture that collaborative spirit in which we work.

Lauren

Much of arts management is about taking risks and using your intuition; you feel this is the moment, like this feels right, you know, it’s a lot of gut reactions.

Ilknur

Often times it feels like, “what have I gotten myself into?” Other times it’s like, “I’m so glad I’m doing this and I want to do more.” We always knew we wanted to do this project, we just didn’t know when. Then we saw a space at the Ford building, and realized it’s within our budget because all the businesses were closed due to the pandemic and lockdowns. So we signed a lease for one year at a rate we can afford since we’re running the entire out of pocket. Next year, the prices will go up and we might need to evacuate.

There’s this toiling away, working and working for something you believe in. But then again we are social creatures, and we do need that encouragement. We want to work with people who believe in the project, and we can build it together. That’s why I want to thank you, because you understood the idea from the very start.

Lauren

It was so fun sitting and working with you in that capacity back at ChaNorth, and being able to share the knowledge of what a nonprofit can do and how it can push a project forward. You know, many galleries never lift off the ground so quickly. And I think that you two had a really solid foundation to start and it’s just so amazing to see where it’s come through this time, especially through a pandemic.

Vuslat

We’re thrilled that we have you and also Luis in our inaugural exhibition. And I think it’s just the perfect combination of everything coming together at the right time. The theme was something we had been thinking about for a while, and I think that also resonates perfectly with the poetry that’s in your work. I’m curious, what’s next for you? I know you’re keeping busy. Can you tell us a little bit more about your next project and how we can keep up with your news?

Lauren

I’m currently obsessed with time and how places change over time. When I started the Architecture of Memory series, I documented how conditions were changing from place to place, like the high desert versus deciduous forests versus grasslands versus tundra. And, then when in residence [in Oregon and New Mexico], I was in those moments wishing I could come back and visit the site again and just see how each of these environments changes over time.

I’m working on a project here in Prospect Park, Brooklyn, where I am documenting the same location within a 12-month period. I started it in January of this year [2021]. As the project evolves, I’m noticing different patterns that I’m wanting to dive further into to develop installations at some point: the changing color of specimens within the park in this particular space and particular time. It is going to become a wall-based installation; probably a multipanel polyptych of sorts documenting color and time. I’m finding that it’s probably going to turn into a multi-year project.

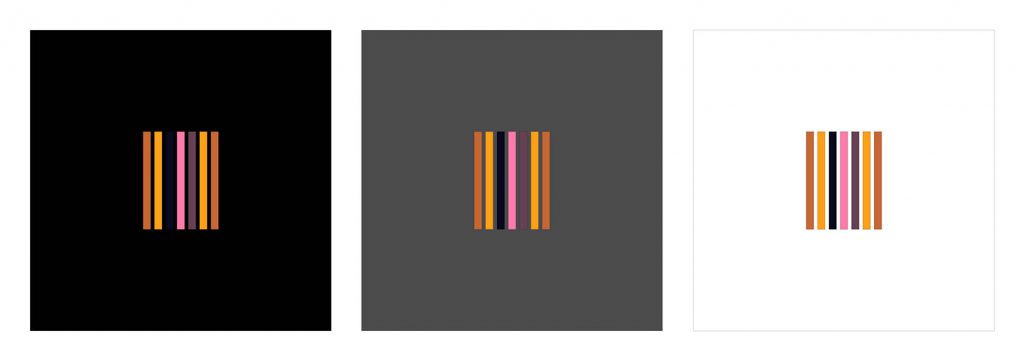

I’m also working on the mind.s.pace project which is translations of words or phrases into color against different colored backgrounds. I had asked the question of my cohort in Playa, “what color is your mindspace.” When you close your eyes, what color do you see in your mind’s eye? People perceive different colored mindspaces–red, green, purple, for instance–some people have multicolored mindspaces, white mindspace like staring into the light at the dentist, but mine is black. This project has more than 70 entries thus far, each as part of a triptych: one on a black background, one on a gray background, and one on a white background printed on aluminum.

When you both first invited me to be a part of this exhibition, we were speaking about the pandemic and endurance. Since we [humanity] were home all the time, one of the things I found comforting was the simple domestic act of doing dishes. I was taking photographs of my dish rack every day, which is another way of tracking time, slowing down and quieting the mind. When I was feeling stressed the dishrack was very organized, when I was feeling a little more free, it was much more precarious in the stacking of dishes. I’m hoping to eventually turn this into a flipbook.

Vuslat

Thank you so much, Lauren, Thank you again, for giving us your trust, and for giving us your time, and for giving us your art. It really is an honor to open the exhibition with you and Luis and Ilknur.

Ilknur

Yes, definitely. Thank you both so much for this wonderful conversation. I’m so looking forward to seeing where our projects take us next. Thank you.

Lauren

Thank you both for inviting me to participate in your inaugural exhibition and this conversation. It is such a pleasure to be speaking with you at this crucial moment in MinEastry of Postcollapse Art and Culture’s journey. Congratulations again!

About:

Lauren Alyssa Bierly is an interdisciplinary artist and researcher whose artwork is rooted in phenomenology and inspired by ecology, language and architecture. Bierly has exhibited in New York, Oregon, Kolkata, and Moscow. She was artist-in-residence at Playa: Art + Science; ChaNorth Residency; Starry Night; Panoply Performance Lab and Trestle Art Space. Bierly earned a Bachelor of Architecture from Pennsylvania State University (2009), and MA in Modern Art, Connoisseurship, and History of the Art Market from Christie’s Education (2010).

Copyright © 2021 MinEastry of Postcollapse Art and Culture.