MPAC in Conversation with Yulia Pinkusevich

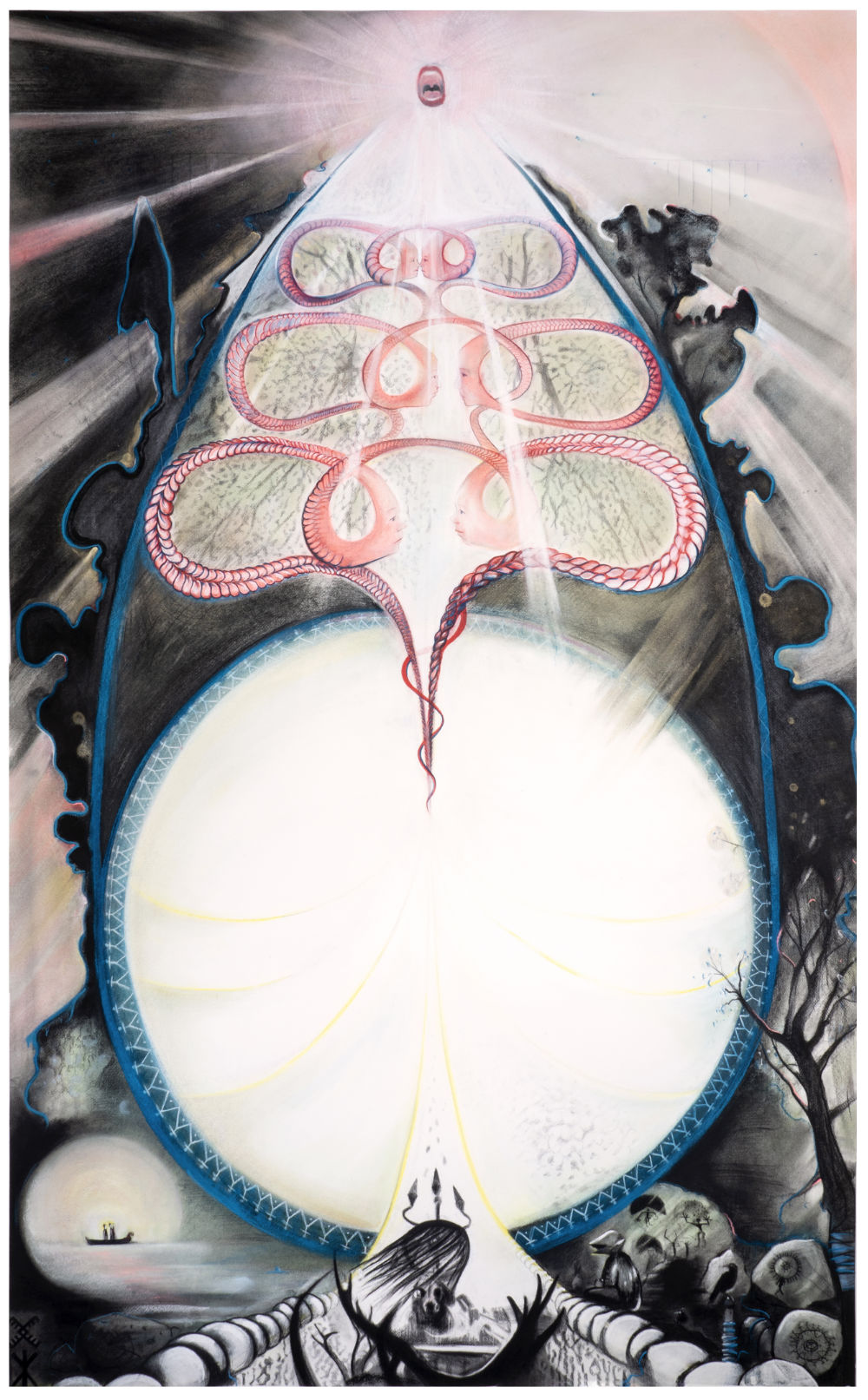

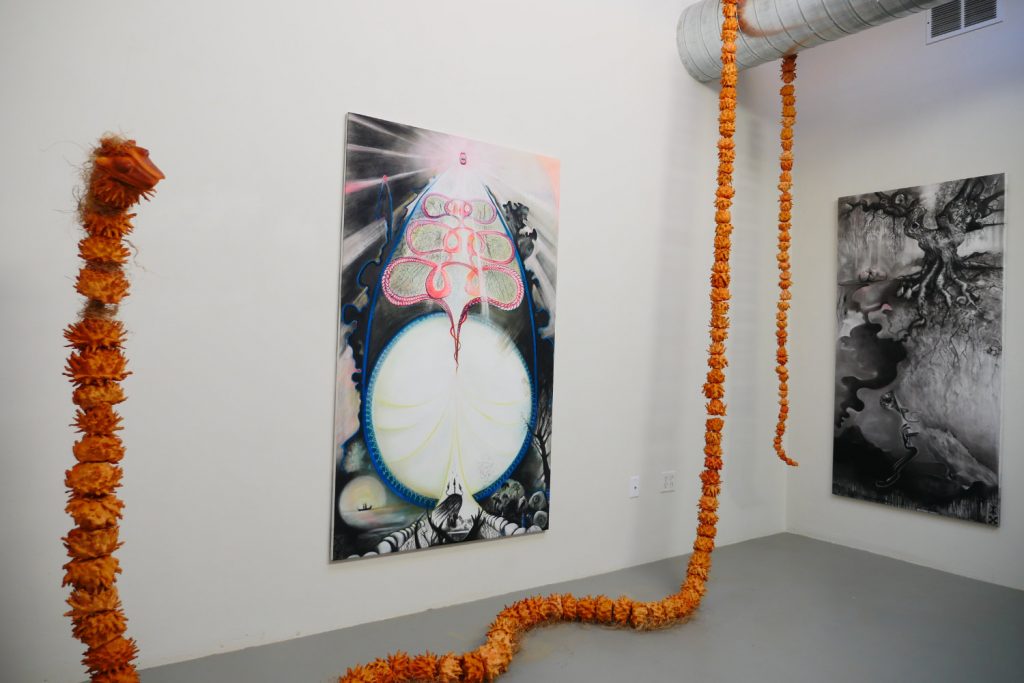

It’s a pleasure to introduce Yulia Pinkusevich, the artist of our current solo exhibition Sakha Aesthesis. Pinkusevich, who primarily creates drawings, sculptures, and installations, focuses on site and the psychology of place, investigating questions that conceptually unfold from this research. Her large scale works often engage the body of the individual viewer, visually pulling in and inserting the viewer into the transformative spaces in the work. Pinkusevich’s contemporary practice is influenced by architecture and industrial aesthetics, folk art, petroglyphs, Japanese woodcuts, Russian Suprematism, ecology and scientific imagery. Sakha Aesthesis presents four paintings and a serpentine sculpture from Pinkusevich’s Sakha series. The exhibition is on view from July 23 to September 29, 2021 at the historic Ford Building in Portland, Oregon.

"When stalin’s regime systematically purged shamanism (and all other religions) in the 1920s, a multigenerational amnesia around native heritage and sacred practices afflicted the region."

Vuslat D. Katsanis: Could you say more about your practice? As far as I’ve come to know your work, you’re known for your large scale and site specific works that emphasize both the experiential quality of art viewing and the materiality of the artistic process. Could you speak about your choice of scale and material, and how you conceptualize those decisions?

Yulia Pinkusevich: My impulses and aesthetic come from several sources. I was born in the Soviet Union, where art and graphic design was used as a political tool. Social realism was everywhere and it served to propagate certain political agendas. Artists like Aleksandr Rodchenko and Liubov Popova and Kasimir Malevich made a lasting impression on the Soviet aesthetic and by the 1980’s this Constructivist style of visual language was ingrained in most of society. Growing up in such a specific visual environment had a strong impact on my early aesthetic. Then I immigrated to New York City, a place where the scale of things is massive and so much visual information comes at you at once. As a young artist growing up in New York, I wanted to make an impact, to be noticed, to shift my work into architectural scale and create immersive environments.

Ilknur Demirkoparan: What you said about scale and your influence from the Soviet era—seeing those big monuments, and the use of space to communicate a certain political system—is fascinating. We see the same visual strategy used in New York but for another purpose. All those massive, loud, and colorful advertisements really show how society here is structured around the idea of competition. One has to compete even to be seen or recognized. Contributing to your society is not enough. Ironically, both systems suggested their path is better. Communism was supposed to be the alternative where the individual was seen and valued.

Yulia: Yes, I think most people who’ve lived within both systems can see the pitfalls of both capitalism and communism. I’ve spoken before about the jarring shift of going from extreme communism to extreme capitalism, an experience which challenged a lot of my beliefs about the world. It also helped me experience the subjectivity of history and education. As a young child, when you are told a story, you tend to trust it, trust your textbooks, your teachers, and the dream of it all. But when you hear the same story told in a completely different way, one which omits everything you’ve learned before, you realize that history is just another biased narrative. Therefore I think that duality of identity continues to have a huge impact on how I function in the world. Inherently, underneath it all, my art functions as a tactile way to explore the philosophical, the intangible, the dualities of life.

Ilknur: Speaking of perspective, when we think about the evolution of one point perspective in western European Art, we can find the influence of Christianity. If human men were made in God’s image, naturally, his eyes would see like the divine. That was really a philosophical drive of religion and that one point perspective told the ultimate truth. Whereas in most non-Christian cultures, for example in cultures immediately adjacent to Europe, like Persian or Turkish, there is no discernible perspective. In those works, everything appears to float, because they’re more interested in expressing time, which isn’t connected to perspective. In fact, if the attempt is to narrate how things have happened, it has to be freed from perspective. This is how miniature painting evolved, through that thinking, yet they were also trying to see like the divine. This has always been so fascinating to me. And now that we are rethinking our contemporary moment through decolonial aesthetics, we question how we see things. How can we show things the way we see things?

Yulia: I resonate with this shift in perspectival theory. During the Renaissance, the Western rules of perspective came to define individual points of view. No longer the omniscient perspective; this human centered perspective centers the individual, the rational, the logical. But I’m drawn to art from Asia from that time period for the opposite reason. For example the 72-foot long 17th-century Chinese scroll entitled The Kangxi Emperor’s Southern Inspection Tour (1691-1698) created before western perspective was introduced in China. The scroll shows scenes from many perspectives. The viewer can see both above and below and over and under creating a dynamic composition and viewing experience, one that is more closely associated with the divine perspective or omniscience. I take some lessons from these masters. My own work never follows rules of perspective, in the true mathematical sense. I’m interested in working with forced perspective, but also in breaking the logic of it, to make spaces that bend to my will. Works in Sakha Aesthesis very much engage with this idea of multiple perspectives. Most of the paintings in that series have two horizons, they have shifting scales, and multiple perspectives. It’s a way to go beyond the realm of possibility for me.

Vuslat: Would you tell us what motivated you to start your Sakha series? You had shared the story that your mother passed onto you about your family and history. In your artist’s statement, you describe the repressed memories and a series of erasures occurring on a political level during the Stalinist era. How do your Sakha series consolidate that history with your own take on contemporary art?

Yulia: We all had a lot of plans in 2020, moving fast, going places, doing things, and I was no different. Suddenly things changed, here we are 18 months into a global pandemic, being asked to stand still. This pandemic also coincided with my sabbatical year and most of my planned travel and projects were canceled, leaving me with no deadlines to work towards. Therefore I had the rare opportunity to slow down and reflect on my work and my life, allowing for slower and more personal work to come to fruition. Around this time, my mother shared a video of Siberian throat singers from Yakutia, explaining that this is a tradition from our Siberian culture. I learned then that my maternal ancestors were Indigenous Siberians who (likely) practiced forms of shamanism in the Sakha region of Russia. This history was almost never discussed in my youth and it awakened something in me. It rekindled my desire to connect to this land and its traditions, to embrace feminine intuition, and to look for answers from ancient wisdom. All of this happened while I was adjusting to life as a new mother and reflecting deeply on my family history and the lives of my Siberian ancestors. Because native Siberians were brought to the brink of extinction by Russian settlers in the nineteenth century, very little Indigenous culture remained by the time I was a child. When Stalin’s regime systematically purged shamanism (and all other religions) in the 1920s, a multigenerational amnesia around native heritage and sacred practices afflicted the region. For my family, this amnesia left only the remnants of what seemed like strange, forgotten superstitions. Seeking to both reconnect with my lost heritage and contribute towards healing the planet, I began to learn about Earth Living Systems and Gaia Theory, scientific insights built upon Indigenous cultural knowledge, the practice of bio regeneration, and sustainable land stewardship.

This ongoing research has led me to expand my knowledge and reframe my own beliefs about thriving pre-colonial civilizations. The Sakha series depicts my own journey through time, meditating upon my connection with my ancient Siberian lineage and exploring the spirituality of my ancestors as a source of inspiration and life. Thus, during this pandemic-sabbatical with no eyes on me, no deadlines or external pressure, I gave myself permission to spend time with this research and see what manifested. One day this work came through. I had a vision for three paintings about the three spirits that embody each individual: the earth spirit, the mother spirit, and the air spirit, which the Sakha people believe exists in all beings.

Vuslat: When I saw your work in person, I was in awe. Seeing them in person, especially how you installed them in the space that we have, brings about a whole new experience. You have this really kind and very smart way of inviting an unfamiliar audience to experience what we call “decolonial Sakha aesthesis.” What Walter Mignolo and the decolonial group of scholars critique in their dossier for Social Text is the flattening of the senses in favor of promoting a singular, rational, hierarchical understanding of taste and sensibility, and with it, the loss of the possibility for accessing other knowledges, practices, and values for thinking the future.1 What I see in your work is an undoing of that flattening.

Your work—and you’re doing this very gently, in a poetic way— invites even the most skeptic or the unlearned, into that multisensory experience of living-knowing-learning from the natural world. You guide the viewer’s eyes to experience, not command, nature. And the giant, 30-foot serpent sculpture confronts our own smallness. It’s humbling. Thinking about your work and writing about it through the framework of the Mignolo group, I did some more reading. I was happy to read the work of Madina Tlostanova, a professor of postcolonial feminism who teaches in Sweden. In a conversation she had with Mignolo, she talks about the urgency of acknowledging silenced knowledges not as a sort of “exotic exercise of affirmative action,’’ but as a matter of responsibility, and I would even add, as a matter of debt.2 Tlostanova links the colonial Arctic inhabitants in Central Asia, the former colonies of the Soviet Union, directly with decoloniality as a praxis. So the path you have intuitively followed through your Sakha series finds context as part of the larger decolonial political intervention wherein that specific geography of the Soviet Arctic is named as the essential link.

Secondly, considering how subjugated knowledges or erased histories then get relegated to the realm of folklore or mythology as something marginal and not quite up to par with what’s presumed to be contemporary art, the task of decolonial aesthesis become a more urgent one to break those hierarchies. Here I would also add the question: whose contemporary? We’re talking about these multiple contemporaries coming out of formerly colonized populations across Central Asia, the Turkic populations, and the former Soviet Union and their wider reach across the Global South. So what I’m thinking about your work and your multi-positionality as an artist, a professor, a mother, and also your identities as part Jewish from Ukraine, and part Siberian Yakut, and New Yorker and Californian, is the complexity of what you offer. And I wonder how that complexity is received in the US, or even what hesitations you might have had in sharing it, given its noticeable difference from your earlier body of work?

Yulia: It is true, I struggle with how to clearly define my blended identity. Part of my hesitation in sharing this work initially was embracing its soft power and feminine aesthetic as well as the spiritual aspects guiding this work.

"This body of work really came from the heart"

For a long time, probably due to my western male centered education, and my observations of the art market in New York city, my conditioning made me perceive that work which had an overtly feminine aesthetic was lacking gravitas critically. This of course is false and this assumption is due to centuries of female oppression, but I recognize that it is hard to erase centuries of conditioning. Thus as a younger artist, I embraced the masculine vibe, reduced my work to be minimal and monochromatic, which formally still appeals to me. But, I think during this pandemic, especially after becoming a mother and experiencing the career setbacks of that shift, I stopped caring what others thought and finally embraced my own feminism. I’ve always fought for women’s rights, and I certainly believe in gender equality. But I realized that in my own art, I was holding back, and I think slowly, it’s been moving towards ideas and projects that are closer to my heart, not just my intellect. This body of work really came from the heart. I truly did not consider anyone else when making this work. I honestly didn’t think anybody would want to show it, so I made it for myself and for my daughter. I felt compelled to make it and because I had this time, I gave myself permission to do it. I did not share any of this work at first, but almost a year into the work, I posted a couple of images on social media and noticed that a handful of respected artists in my community were very enthusiastic about this work. From there I was offered two solo shows (one with Postcollapse) and the work has been included in two important group exhibitions. This helped me be more brave about sharing this work.

Vuslat: I’ve started seeing art publications, either reviews or popular culture publications about art, with titles like “shamanism is making a comeback,” or “contemporary artists turn to the spiritual,” which is both fortunate and unfortunate. It’s fortunate because that practice and aesthetic was always there but is finally finding recognition in North America. Yet it’s unfortunate because they seem to be marketed as yet another trend. What we see in your work, however, and in the decolonial aesthesis project at large, is an invitation to access a body of knowledge or a vantage that was long withheld from the realm of contemporary art. For that knowledge to have emerged from your time during the lockdown as a new mother and recently tenured professor, listening to your intuition that it is what others might benefit from, is something we don’t often see in the North American art scene.

Yulia: Yes, I too have noticed this trend. Maybe our culture has become so overworked and capital obsessed that it’s losing sight of what art is really about, right? In a lot of ways, the art market is a giant stain on the purity of art. I think conflating success as an artist with market success can really confuse artists’ intentions. Artists make work to connect with each other and the larger world. The artist, like the shaman, is essentially a person who can connect to both the physical world and the spirit world. The practice of creating art has some connection to the practice of shamanic ritual in that art functions to create meaning in life, which is akin to rituals performed for healing or spiritual connection. People are finally acknowledging artists that have been doing this work all along, partly because there is interest in Indigenous practices and decolonial aesthetics.

Ilknur: So many of those online gallery platform newsletters are structured similarly to fast fashion shop marketing emails. In the morning you get “eight new trending artists to collect,” in the afternoon another email blast alerts you to “ten exciting artists working in blue.” They forge these superficial relationships between artwork and artists for marketing purposes. Such collapsing of aesthetics and flattening of their intellectual depth works in favor of capitalism.

Yulia: Some galleries do a very good job caring about the story and talking about the important issues, like you two for example. You really care about the meaning of the work and you’re in it for a higher purpose. But there’s a real need for artists to eat, pay bills, etc, so we too need to make some money. We can have more government funding for art and private public partnerships to support arts in the community. Some of these structures already exist but lack public buy-in. In my opinion funding the arts is a matter of convincing the masses that investing in your art community is a viable long term investment strategy, ones whose returns should be measured in cultural capital not dollars and cents.

Vuslat: Your work opens to this whole new way of thinking. I’m really grateful that my sister first gave me your name as we were grappling with putting into words the connections across postcollapse societies from East Europe and Central Asia and their widespread global diasporas, especially how they manifest among immigrant communities in the US. Through your work, I discovered this other branch of scholarship on the links between the Global South and the post- and anti-colonial struggles of the peoples from the former Soviet Union, and specifically, the work of Madina Tlostanova, who focuses on Central Asian and Siberian ontologies, epistemologies and ethical and aesthetic systems. And really the question to ask at every turn is how to think about contemporary art through decolonial aesthesis? Not just as a trend described in those “shamanism is making a comeback ” type of articles, but really as a philosophical mode of engagement with the world to reevaluate how we understand ourselves and our relationship with everything that we’re a part of.

This relationship is not limited to the human, or at least the kind of Eurocentric humanism that isolates and privileges humans over all other beings. It is wonderful to see that complexity in your works through their scale and because of their conceptualization of space. Your paintings lend an entryway for the viewers to experience what they offer, such that I am compelled to think about the history of single-point perspective, as well as the critiques of both humanism and posthumanism. Those who critique posthumanism are precisely the ones to whom the dignity of humanity has been, and continues to be, denied. We’re living in a country, arguably one of the most developed in the world, where people have to defend their right simply to exist, and having to do it through hashtags. The word injustice isn’t enough to describe the racist matrix that the North American and Eurocentric humanism has normalized.

So I’m thinking about your work in relation to this discourse on what has happened in the US over the recent years and the deep fissures that came into visibility during the course of the pandemic. When I enter the space in your work to rethink my humanity and potential, I realize that other options are both possible and within reach. It’s really a profound experience.

Yulia: I appreciate hearing that. We, as artists, make the work with certain intentions, but when it goes out into the world, you have no control over how it’s interpreted. I’m deeply pleased to hear that some of the things I’ve been thinking about translate. I tend to shy away from being overtly political in my work, but inherently politics are always present. The systemic inequities in this country are very visible in a city like Oakland. As I witness the daily struggles of my house-less friends, I recognize my own luck and immense privilege, yet because of my blended identity, refugee status and immigrant experience I also have, and continue to identify with the “other.” America is facing a (long overdue) reckoning, the pervasive systemic racism must be acknowledged collectively, if we are to ever heal as a country and work to fix these deep wounds and inequities.

Ilknur: Would you please tell us a little bit more about the spirit worlds as well as the newest piece in the series, the serpent sculpture?

Yulia: As I mentioned, when I started doing this research and reading about the Sakha traditions, I learned that Siberia is a pretty extreme place, with extreme weather. The sun never sets in the summer and then it stays dark for many months out of the year. So naturally, this culture worships the sun and summer solstice is the biggest holiday of the region. I found it really compelling that in Sakha beliefs, every single person possesses three spirits that aid you in your life. The first is the Spirit of the Mother, this spirit is passed on through the Father, and enters the child in the womb upon conception. This divine maternal spirit is present in all genders.

Traditionally Siberian women gave birth on the ground. When a child was born upon touching the ground, the Spirit of the Earth would rise up and enter the child, solidifying a connection to the earth, the roots of the trees and the soil, connecting to the lowerworld. Then upon the baby’s first breath, the baby cries and the Spirit of the Air enters. This connects to the upper world or the celestial realm. I love this notion and feel that we humans do possess these connections; though we certainly aren’t always aware of them. There are ways that we’re grounded, there are ways that we’re cosmic, and there are ways that we hold this maternal care. Personally, I like the parallel of thinking beyond the individual, that we all share some connection across all beings.

I also researched ancient artists from that region, looking at a lot of petroglyphs that depict these very strange, human-like creatures that have glowing orbs for heads, radiating forms, and it’s just magical! I used some of that found symbolism, and gave myself permission to interpret these images and symbols with some creative license, without feeling too attached to historic accuracy. My research centers around learning about the lives of Siberian women during pre-Christian times, where, feminine values were perhaps a bit more respected.

That’s the story behind the first three paintings. The fourth one is about fractured identity, both in the direct sense of being an immigrant and holding two cultures simultaneously, as well as the fracturing we feel when separated from nature. It is about the reintegration of our disparate souls whether in terms of our human selves versus animal selves, or our immigrant selves versus our Indigenous selves, or even our intellectual selves versus our feeling and sensing selves.

The sculptural serpentina was all about animal spirits. I was recently reading interpretations of Egyptian hieroglyphs, and the story of Osiris and Isis and how it very much connects to the Christian mythology of immaculate conception and the virgin birth. When thinking about universal symbols, one of the most common ones is the snake. In Christianity, the snake is a symbol of temptation, or evil, but in pre-Christian traditions, the snake represents the world. In ecological terms, the snake is an essential part of a local ecosystem. Finding snakes in your garden is an excellent sign of a healthy garden. Again we see this duality of good vs. evil, masculine vs. feminine. I wanted to reinstate this duality and make work made from the earth and of the earth. I ended up working with all natural, biodegradable materials, which I primarily grew in my own garden. I worked with plant cellulose, paper mache and terracotta. The serpentina is both silly and inviting yet sharp and unruly.

Ilknur: She is also uplifting.

Yulia: Exactly. There’s an ecstatic aspect to my work, but a lot of my work can be very heavy. A lot of it deals with death and destruction and can be psychologically heavy. This work is not about that. It’s about love and life; there’s hope in it. It’s also silly and there’s something a little funny about it. It’s been nice to find that people who I respect, artist and curators, are seeing value in this body of work.

Vuslat: We, at the Ministry of Postcollapse Art and Culture, certainly value humor as an essential part of both resilience and endurance. We love your work. Thank you so much for sharing it with us.

Ilknur: Thank you so much. We’re excited to see the future of this series.

Yulia: Thank you. It’s been a wonderful opportunity.

- “The Decolonial AestheSis Dossier.” Social Text Online. July 15, 2013. https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_topic/decolonial_aesthesis/.

- “On Other Possibilities for Philosophy and Humanity: Madina Tlostanova in conversation with Walter D. Mignolo,” EastEast. https://easteast.world/en/posts/84.

About

Yulia Pinkusevich is an artist and educator born in Kharkov, Ukraine (USSR). Upon the collapse of the Soviet Union, her family fled the Eastern Bloc as refugees, immigrating to New York City. She holds a Masters of Fine Arts from Stanford University and Bachelors of Fine Arts from Rutgers University, Mason Gross School of the Arts. Yulia has exhibited nationally and internationally including sitespecific projects executed in Paris, France and Buenos Aires Argentina. Yulia’s art is in the public collection of the DeYoung Museum, Stanford University, Facebook HQ, Google HQ and the City of Albuquerque. Yulia is currently Associate Professor at Mills College in Oakland California, she lives and creates works on unceded Ohlone territory.

MinEastry of Postcollapse Art and Culture (MPAC) is an artist-run space and think tank dedicated to exploring our global contemporary from the vantage of postcollapse art and theory. Our frames of reference begin with the human experiences from East Europe and West and Central Asia since the fall of the Berlin Wall but permeate to every corner of our diasporic worldpresence.

Edited by Vuslat D. Katsanis. Copyright © MinEastry of Postcollapse Art and Culture. 2021. For permissions contact [email protected]

Comment (1)

Comments are closed.

Pingback: Mother, Earth, Air: Yulia Pinkusevich and Sakha Aesthesis at MPAC | Femme Art Review

September 22, 2021