In Conversation with Daniel Rosca, Artist and the Director of the Bucharest Biennale

Recently, I had the pleasure of sitting down with Daniel Rosca, a Bucharest-based artist and the newly appointed director of the Bucharest Biennale. We discussed his unexpected journey into this new role and the biennial’s legacy of bold curatorial experimentation. From public voting initiatives to the introduction of an AI curator, the biennial has consistently pushed boundaries, exploring themes of democracy, inclusion, and the evolving relationship between art and society.

Our conversation also touched on Rosca’s artistic practice, which is marked by symbolic and emotionally charged works that transform environmental issues—such as deforestation and water pollution—into visceral, abstract forms.

Ilknur Demirkoparan – You are an artist, but you are also the director of the Bucharest Biennale. Seeing an artist in this role is really exciting for me. How did this happen?

Daniel Rosca – It’s an interesting story because I wasn’t really looking for this position. I’m friends with Eugene Rădescu, one of the co-founding directors of the Bucharest Biennale. I offered to assist him with this edition because he was retiring and there was a lot of work to do. After a month, he asked me if I would want to take over the director role. It came as a surprise, and I initially declined, as my intention was simply to assist him. I recall asking him if he was sure that I was the right person for the job because I usually prefer to be in the back, but eventually he convinced me.

ID – That’s an amazing story. Being chosen as the new director by the very founders who built it over the last 20 years is such an incredible honor. It really shows how much they trust your vision and leadership to build on that legacy. Big congratulations!

DR – Thank you. It is a big responsibility, and I learned a lot from working closely with Răzvan Ion and Eugen Rădescu, who are the original founders of the Bucharest Biennale and have been directing it since its inception in 2005. It’s also been an incredible experience having Beral Madra, the founder of the Istanbul Biennale, on Bucharest Biennale’s advisory board.

It has also been great working with so many people who volunteered their time to make this edition possible. From those who helped with the website, writing texts, and organizing the exhibitions to the teams handling the venues and spaces—so many people have contributed, and it’s been inspiring to work alongside them all. I am happy for this opportunity.

ID – Quite often, large biennials are criticized for presenting thematic questions with predetermined answers and selecting artists from established networks, rather than seeking new voices and fostering conversations. On the other hand, when I think about the Bucharest Biennale, I think of the unexpected, and the surprising. Whether this is because of its smaller, more intimate scale that creates a more immediate impact, or because the curation process embraces experimentation, and discovery—I can’t quite find the perfect word to describe it—but the Bucharest Biennale feels like an anti-biennial biennial. What are your thoughts?

DR – In a way, yes, we approached it with the mindset that this is a smaller biennial and will always remain one. We didn’t want to emulate something on the scale of Istanbul or Berlin, which are much larger and operate differently—not just because of their resources, but also because keeping things smaller allows for better control over the outcomes.

This year, for example, we decided to take a unique approach with an open call and public voting to explore the democratic process. The idea was partly inspired by the fact that there were so many elections recently—in Romania, across Europe, and even in the U.S.—and by the current democratic challenges in many countries. In Austria, Hungary, Slovakia, and elsewhere, the rise of the far right has created a lot of turmoil. So, we thought it would be timely to explore this issue.

At the same time, this approach was also a kind of social experiment—to see what the public would choose. To be honest, I was a bit nervous about how it would turn out, but in the end, I think the public made some great choices. People seemed happy with the selected artists, and the works in the exhibition turned out really well.

Another goal was to break down barriers. As you mentioned, biennials can feel like closed circles, making it hard for new artists to break in. We wanted to create an opportunity for those who might not usually have a chance to participate, and I think we succeeded in opening some doors for them.

The biennial has always had a bit of a political orientation, and this year's edition was no different. It’s always been about addressing issues, whether it’s about democracy or other social concerns.

ID – You are also operating on a small budget. It’s been quite a while since the Bucharest Biennale was established, so why do you think there’s still no significant interest from the government to invest in it? I know that’s a big question, but I’m curious why that is.

DR – Because they don’t really care. Like you said, it’s a lot about connections. They tend to prefer funding more popular or mainstream arts rather than a biennial. I mean, we did receive some funds from the local government—specifically from City Hall in Bucharest—but that’s about it, and it wasn’t much.

Otherwise, it’s really difficult. To be honest, a lot of people working in the state don’t even know what a biennial is, so they don’t see its importance. Interestingly, the Bucharest Biennale is much more recognized internationally than within Romania. Outside the country, you’ll find articles written about it, and many people know about it. But within Romania? Not so much.

There are also companies that don’t offer support because events like this don’t attract as large a crowd as commercial events, like music festivals, which bring in tens of thousands of people. Since this is a smaller event, it’s not as appealing to them. However, we manage to make it happen with the help of people who work purely out of passion. Many individuals contribute a lot of their time and effort for free just to help us make it all come together.

ID – Knowing more about the circumstances, makes it all the more incredible.

DR – Yeah, they did a really great job, Eugen and Răzvan. They also struggled a lot to make it happen—there was so much work involved. But it all came from their passion. They really wanted to do something for Bucharest, for Romania, and to change people’s way of thinking. They wanted to show that we can create something meaningful too, promote something different, and highlight important issues.

The biennial has always had a bit of a political orientation, and this year’s edition was no different. It’s always been about addressing issues, whether it’s about democracy or other social concerns. I don’t think art is just about appreciating a nice painting and leaving it at that. Art should spark discussion—it should open dialogues about the world we live in. I believe art and society are intertwined. Artists can’t just live in isolation, in the clouds; they are a part of society and have an ethical responsibility to contribute.

Art is a reflection of society, and if you look at art from 100 years ago, you can get a sense of the times, of the issues that were at play. In the same way, today’s art shows us what is happening now, what we’re grappling with.

I think as an arts or culture manager, it’s our role—even if it’s just a drop in the ocean—to contribute that drop. Slowly, but surely, every drop adds up. I can see the difference in Romania in the past 20 years. It’s a big difference over time.

It’s crucial to stay active and engaged if we want to preserve our freedoms and quality of life in a democracy.

ID – I want to come back to the idea of exploring democracy and voting as the themes of this biennial, especially in the context of what’s going on in the world. The shortlisted artists also participated in the voting system, which by design allowed the artist to self-curate. When I was talking with the artists, I found out that we mostly voted for each other.

As for the general public votes, I was curious about how it would play out. Most people don’t even have the patience to engage fully with something as important as voting for our future—many don’t take the time to read up on a candidate, for example. I was wondering how much time the public would spend reading the submissions. Would they read everything then decide or go halfway and quit? How would that affect the outcome?

DR – So, some people really did engage with the voting process, as I saw from the statistics provided by the program I used. We had almost 14,000 votes, which was a pleasant surprise. I didn’t expect that many. We received 450 applications, but we narrowed it down to about 80, as many submissions didn’t align with the theme, and a few had issues, like being inappropriate or borderline racist. Once we removed those, we were left with around 80, which made the voting process simpler than if we had kept all 450.

We gave people two weeks to vote—long enough for them to participate but not too long that they’d forget. In the end, the process was a success. I was surprised by the outcome, and also by the quality of the works submitted. Honestly, I had my doubts, but it turned out really well.

ID – The previous edition was another experimental first for a biennial, right? It was curated entirely by an AI named Jarvis.

DR – We try to do that as much as we can. Since we don’t have the financial power to create something on a larger scale, we focus on bringing creativity into the process. We find new ways of doing things and experimenting. That’s what’s great about the Bucharest Biennale—it allows for experimentation. You can come up with new ideas that, in other biennials, might not be possible. For example, imagine trying to implement public voting at something like the Berlin Biennale—it would be a challenge. But here, because it’s more of a private biennial, owned by the co-founders, we have the freedom to try whatever we want.

Since we don’t have the financial power to create something on a larger scale, we focus on bringing creativity into the process. We find new ways of doing things and experimenting.

ID – You also have a series of workshops, and outreach programs throughout the duration of the biennial. Can you tell me about these?

DR – Yes, we organized three workshops. One of these workshops was designed for youth and focused on totalitarianism and democracy, a topic I believe is especially important for young people right now. It’s easy to fall into extremist thinking, even to the point of believing that dictatorship might be a better option. This is particularly relevant today, as many democracies, especially in Europe and the West, are facing challenges.

In this workshop, participants were divided into groups—one group supporting democracy and the other supporting dictatorship. Each group created posters advocating for their stance. Afterward, we reviewed the posters together and held a debate on improving democracy. We also explored the nuances, acknowledging that systems have their flaws. I was amazed by the level of engagement, even from 12-year-olds. The response was so positive that I’m planning to repeat this workshop in the future.

These workshops aim to bring young people closer to art while also fostering awareness of how politics influence our lives. It’s crucial to stay active and engaged if we want to preserve our freedoms and quality of life in a democracy.

Another workshop focused on architecture, exploring buildings from different periods in Romania, comparing pre-communist, communist, and post-communist architecture in an interactive format. The third workshop centered photography and video, tied to similar themes.

Education is a vital aspect of our mission as an arts institution. It plays a key role in strengthening society, fostering critical thinking, and empowering individuals. Dictatorships often aim to suppress education, not necessarily by making people “stupid,” but by creating conditions where they are more likely to comply without questioning. We see it as our responsibility to counter that by encouraging learning, creativity, and active participation.

It’s easy to fall into extremist thinking, even to the point of believing that dictatorship might be a better option. This is particularly relevant today, as many democracies, especially in Europe and the West, are facing challenges.

ID – I am also curious about you as an artist. What are the themes and concepts you explore in your work?

DR – My work is focused on environmental and ecological themes, with a particular fascination for the subject of water. It’s abstract in nature, but I aim to convey the “sensations” of environmental issues like deforestation and water pollution through my art.

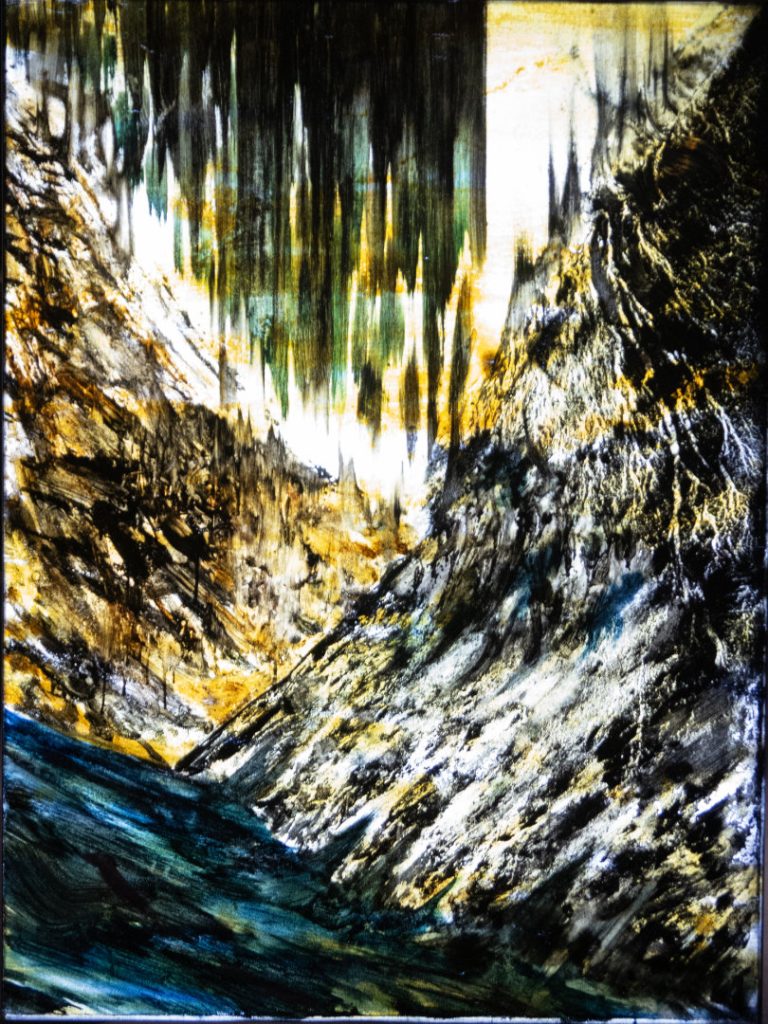

For example, in my recent exhibition Solastalgia, titled after a term coined by Glenn Albrecht, I explored the concept of “the nostalgia of what is to come” in relation to environmental issues. This body of work, which consists of oil on backlit panels, carries a sense of violence and transformation that I associate with the formation of the Earth.

I also have a bit of an obsession with water, which I use as a recurring motif in my work. In another exhibition, I filled the gallery space with water and placed lightboxes on top. The way the light reflected on the water and bounced off the walls activated the space, creating a sensory experience. I enjoy working with water because it expresses so many emotions—when it’s still, it feels peaceful, but when it’s stormy, it feels angry. I believe water can embody all the emotions a person experiences.

Daniel Rosca. “Scorched Echoes.” Oil on canvas and lightbox. 120 x 90 x 5 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

ID – Is this painting from Solastalgia? I see, especially with this one, that there’s a certain violence I can feel in it—not in the conventional sense, but in a way, I imagine the violent processes described in geology, when you learn about how the Earth formed. It’s almost as if, when I think about it in the context of the topics you explore, this piece represents the Earth unbecoming—like a transformation in reverse.

DR – Yes, Like the violence of Earth becoming and unbecoming. Actually, this piece started from a photograph of a burning forest. So, yes, I was thinking about burning when I created it. And that one over there—it’s also inspired by a burning jungle. I took photos as references, but then I abstracted them. I started from a literal image, but my goal was to convey the sensation of it rather than depict trees burning directly

And these pieces, they light up—all of them. They’re made with oil paint applied in thin layers, allowing the light to shine through.

ID – Allowing the light to shine through… That is beautiful.

Daniel, thank you so much! This conversation has been incredibly inspiring. Whether through your commitment to upholding Bucharest Biennial’s founding vision of social responsibility, or your personal work addressing the urgent themes of environmental transformation, it’s clear you’re creating spaces—both literal and metaphorical—that challenge and engage us to think critically about the world we live in.

As we wrap up, I’d love to know: What’s in the future for the Bucharest Biennale?

DR – For the next edition, we’re going to have a curator. We have multiple ideas about the direction, but we haven’t made a final decision yet. It’s possible that we’ll focus on Eastern Europe, but there are other possibilities too. We haven’t finalized anything yet, but for 99%, we’ll definitely have a curator.

We are also looking to expand our initiatives with residencies for both curators and artists. For curators, this means offering opportunities to work with us while also developing their own exhibitions in collaboration with artists. For artists, we want to provide residencies that help them produce art while connecting with experienced curators and artists who can offer guidance and mentorship.

About Daniel Rosca

Daniel Rosca (b. 1991) is a Bucharest-based artist who graduated from the Painting Department at the National University of Arts in Bucharest in 2016. His work has been exhibited in various European cities, including Bucharest, Kiel (Germany), Ulft (Netherlands), Geneva (Switzerland), Paris (France), and Balchik (Bulgaria). In 2017, he co-founded the Grund Association, an organization dedicated to promoting emerging Romanian artists. Rosca currently serves as the director of the Bucharest Biennale (2024).

ilknur Demirkoparan

ilknur Demirkoparan (b. Ankara Türkiye) is a Turkish-American artist whose research-based interdisciplinary practice spans painting, installation, sculpture, digital media, and creative programming to explore identity and memory through image-making, dissemination, and repetition. Demirkoparan is also the founding director of the MinEastry of Postcollapse Art and Culture. She lives and works in Zurich, Switzerland.