Reclaiming (Art)Histories: Citra Sasmita’s Feminist Vision Unfolds

Citra Sasmita’s practice through the lens of project Timur Merah and her recent exhibition Into Eternal Land at the Barbican

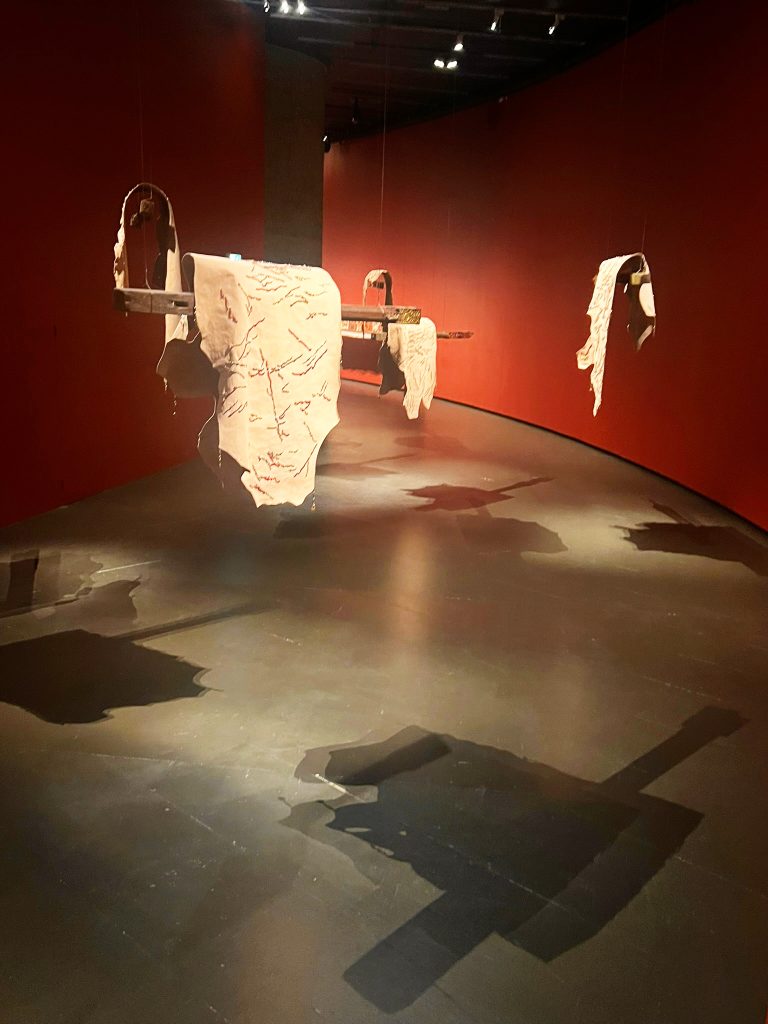

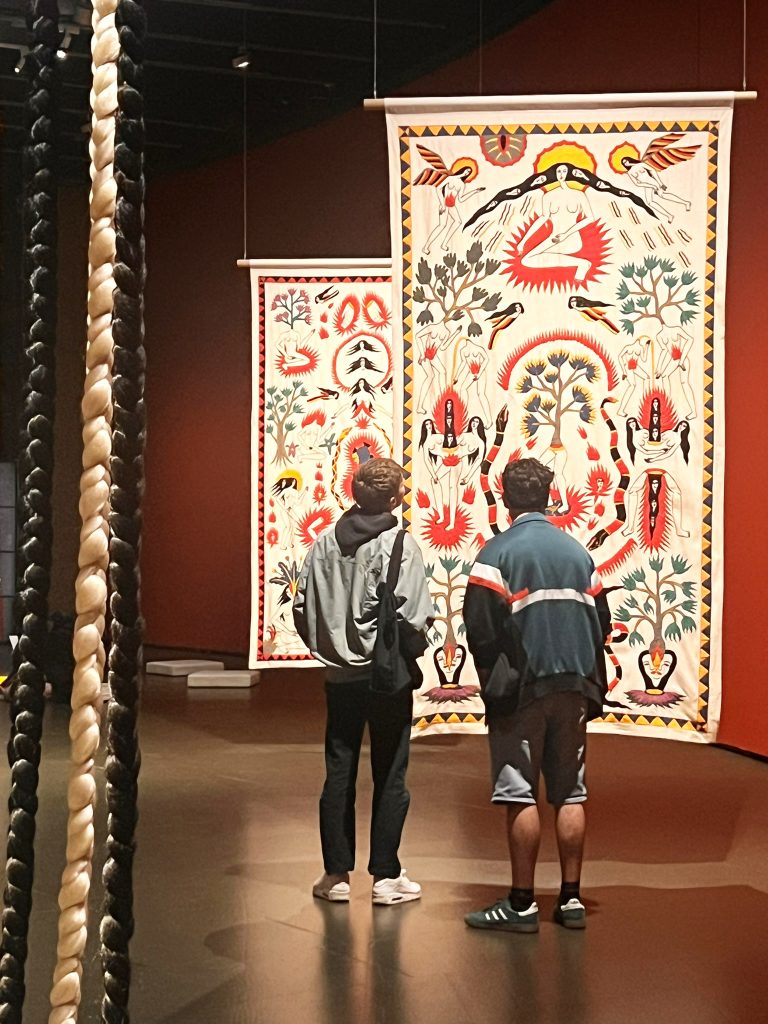

Installation view of Into Eternal Land, Act One, 2024. Barbican. Photos by Elif Carrier.

A geography of black-haired, naked women is intertwined with nature. Trees branch out from their heads and pelvises. Streams of blood spurt from their torsos and the redness of their flesh is exposed. Separated heads, hands, and legs emerge amid motifs of terrain, soil, and ponds. Mutated bodies, half women, half bird, half snake fill the landscape. Encircled by flames, women wield swords. Violence and rage are omnipresent, yet they are overtaken by a profound sense of calmness, and peace within the rich visual language of artist Citra Sasmita’s paintings, embroideries, and eclectic installations. Born in 1994 in Tabanan, Bali, Sasmita’s practice is centered on unravelling misconceptions and painful memories of Bali, rooted in traditional narratives and in the reductive legacy of Dutch colonialism in the Indonesian archipelago.

Installation view of Timur Merah Project I: Embrace of My Motherland (2019), Biennale Jogja 2019: Do We Live in the Same PLAYGROUND? Image: courtesy of the artist.

The reclaiming of ancestral memory through her own vocabulary of iconography and interpretation of the cosmos is anchored in Sasmita’s long-term research-based project, Timur Merah—translated into English as East is Red—which she began in 2019.

The reclaiming of ancestral memory through her own vocabulary of iconography and interpretation of the cosmos is anchored in Sasmita’s long-term research-based project, Timur Merah—translated into English as East is Red—which she began in 2019. Sasmita outlines the foundation of this work in her essay “Timur Merah Project: A Pilgrimage of Narrative, Memory and Historical Legacy.”1 I will thematize Sasmita’s project through two interconnected and parallel research trajectories. The first one focuses on her continued rereading and investigation of historical archives, classical paintings, and ancient manuscripts of the Nusantara, which is the post-colonial Malay-Indonesian archipelago. These canonical texts and ancestral narratives, mostly authored by men, have been transmitted across generations as collective memory. However, they often omit strong female figures or depict women in diminishing roles, while glorifying male heroism. Sasmita’s second research trajectory delves into the layered realities of patriarchy in Bali and confronts the political structures shaped under Dutch colonialism. She traces Dutch exploitation in forms of commerce, the slave trade and exotification of the island, beginning in the mid-16th century.2 Within this historical context, she identifies the brutal end of the Puputan War3 in 1908 as the pivotal turning point marking the island’s colonial history. At this juncture, the Dutch assumed full administrative control of the island, transferring their military aggression into a form of political repression aimed at maintaining control and enforcing its own ideals. In 1920, the Dutch implemented the so-called ethical policies under the framework of Baliseering. Under the guise of preserving an “authentic” Bali, the island was then turned into what Sasmita describes in her essay as a “living museum” that prioritised commercialization while undermining its own rituals and cultural heritage.4 The distinction between high and low art was imposed through a colonial Western gaze that stereotyped Balinese women as an exotic hybrid of nature and culture”5 while systematically devaluing traditional art forms created by local artists.

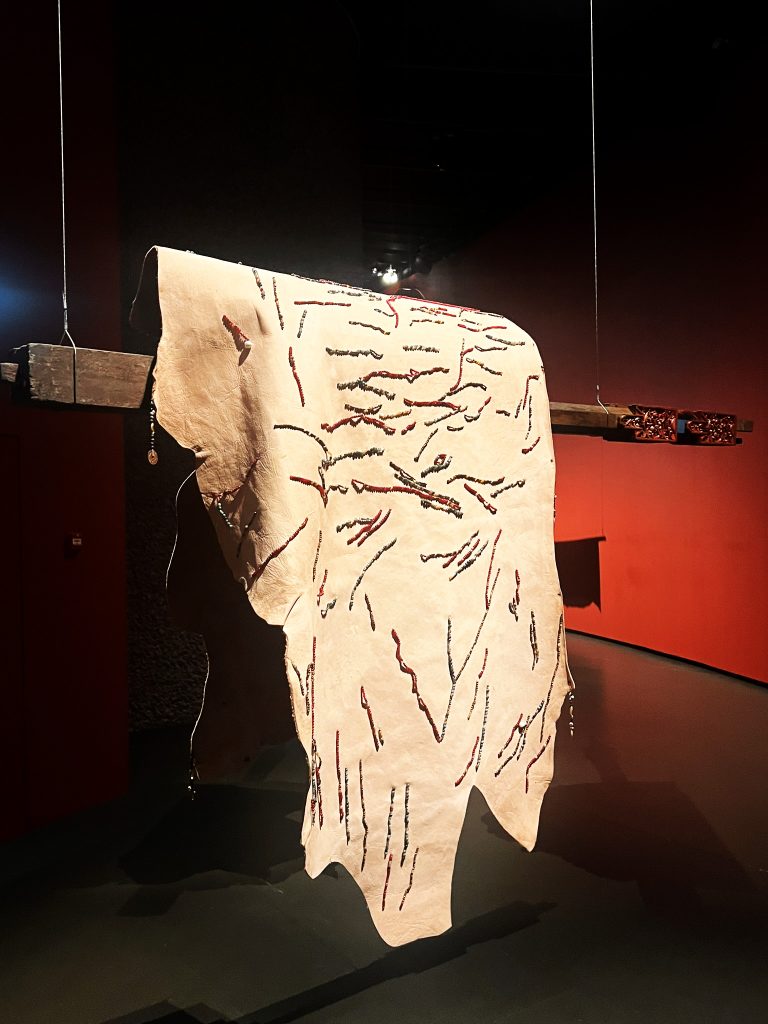

Installation view of Into Eternal Land, Act One, 2024. Barbican. Photos by Elif Carrier.

Under the guise of preserving an “authentic” Bali, the island was then turned into what Sasmita describes in her essay as a “living museum” that prioritised commercialization while undermining its own rituals and cultural heritage

Sasmita’s deep research into reclaiming hidden knowledge, along with her desire to sustain traditional Balinese art forms, led her to train with her teacher, the artist and priestess Mangku Muriati6— one of the most accomplished artists of the Kamasan technique, and one of the few women permitted to practise it. There are only a few women artists practising in this tradition since women were historically excluded from the creation of Kamasan paintings, both in authorship and representation. Dating back to the 15th century and passed down through male lineages, Kamasan scroll paintings tell the stories of Hindu epics, mythology and rituals. Within the narratives depicted in scroll paintings such as the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and Javanese Panji tales, women appear only in supporting roles, serving to amplify the heroic journey of the male protagonists. Their bodies are reduced to instruments of reproduction, and they are depicted as symbols of danger, evil, and seduction—casting only as “sensual entities to be dominated by forces of masculinity.”7 Sasmita, a self-taught artist who studied literature and physics and worked in theatre and illustration before following her passion for art, integrated some of the techniques she learned from Muriati into her practice. Yet she departed greatly in her creation of iconology as well as in her use of bright, energetic tones of acrylic paint instead of the more muted color palette of the traditional Kasaman painting.8 In her paintings, Sasmita radically transforms gods, masculine deities, and the mythological figures with supernatural powers into female figures. This reclamation is evident in her inclusion of figures such as the nineteenth-century poet, queen, and fighter of the Klungkung Kingdom, Dewa Agung Istri Kanya, and Jakarta-based sculptor Dolorosa Sinaga—whose lifelong activism against patriarchy and inequality is inseparable from her roles as an artist and educator.9 These emblematic women take over the roles of male protagonists in Sasmita’s artworks. By doing so, she poses a simple yet powerful question: “What if those ancient texts had featured the important roles of women? Would discrimination toward women continue to this day?”10

Installation view of Prologue, 2024. Barbican. Photos by Elif Carrier

In her paintings, Sasmita radically transforms gods, masculine deities, and the mythological figures with supernatural powers into female figures.

This question, embedded in Sasmita’s ongoing research Timur Merah and rooted in deep historical inquiry, feminist resistance, and visual reclamation, came together on a monumental scale in Into Eternal Land, her first UK solo exhibition at the Barbican, held earlier this year. Curated by Lotte Johnson, the show unfolded in five parts as a symbolic journey through ancestral heritage, ritual, and displacement. The exhibition opened with Prologue (2024), consisting of four cowhides decorated with colourful beads and pearls glimmering like gemstones on the stretched cow skins. Sewn together in irregular lines, these beads resemble abstract landscape forms—roads travelled, rivers passed, and lands left behind. Dutch colonial coins hung from the corners as precious pieces of jewellery alongside beads and pearls. The cow hides were centered on thick antique wooden pillars with aluminium saddles that were attached to the majestically high ceiling of the gallery with thin aluminium strings. The shadows of the cowhides fell across the floor under the dimly lit lights of the exhibition space. They stood still as ethereal beings suspended in space and time—holding on to the ancestral heritage. Prologue was followed by Act One (2024), featuring four eight-meter long Kamasan style paintings on canvases placed diagonally across from one another, with bodies of black-haired women depicting a tale of transformation within two realms—the physical and the spiritual. Streams of fire, water, and blood intertwined within Sasmita’s signature landscape of defiant female bodies. Nature and divine feminine energy collided. Reappearing figures of snakes, birds and flowers stood in solidarity with women as constant reminders of the cycle of life. Snakes, a recurring figure in Sasmita’s works, symbolize the Hindu concept of kundalini—the higher power of one’s self, the vital energy and consciousness of the cosmos, believed to reside at the base of the spine, awakened through transcendence.

Installation view of Into Eternal Land, Act One, 2024. Barbican,. Photos by Elif Carrier.

I have been captivated by Sasmita’s work from the very first moment I encountered it. I stood in front of her artworks, gazing into the faces of her women within a space of ambiguity. How could they appear in tranquility while their bodies are in a state of warriorship—their hands gripping swords, their torsos brutally splitting in two?

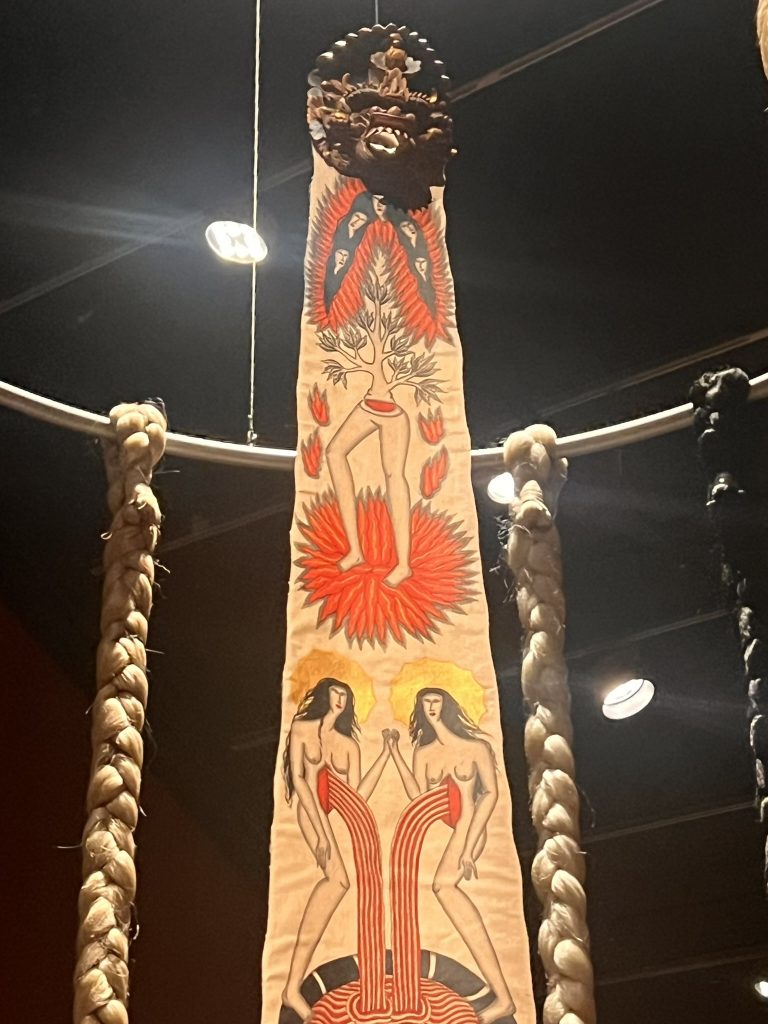

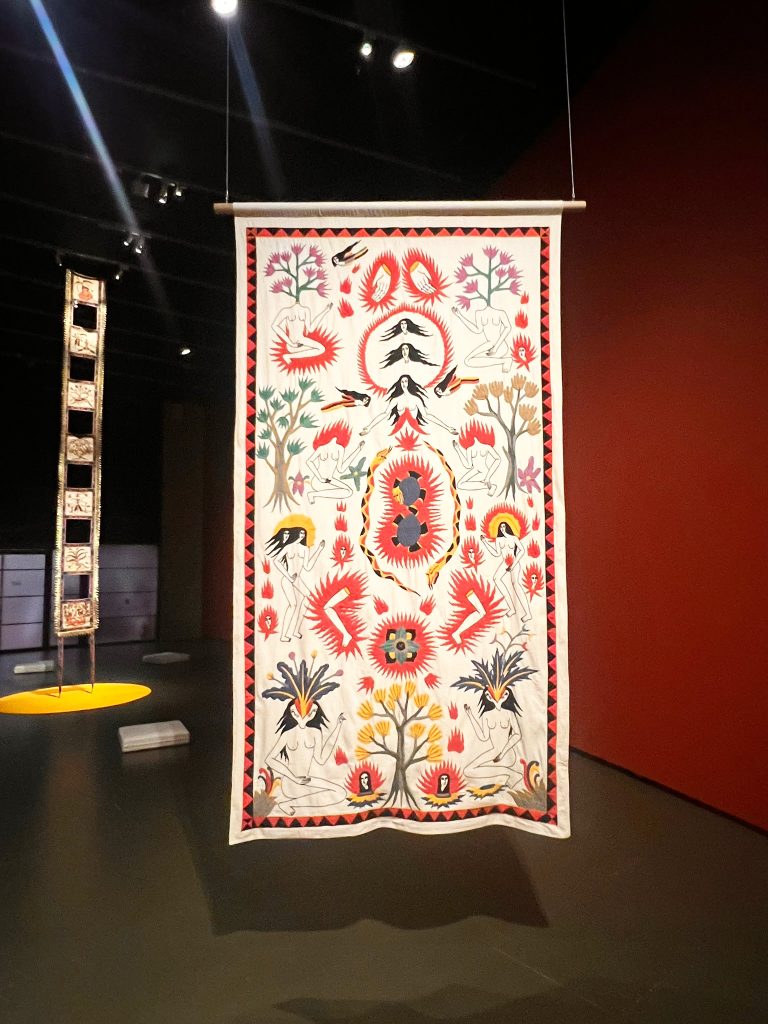

In Act Two (2024), Sasmita created two installations with black and white braided hairs encircling a python skin, resembling a totem painted with her signature motifs. A wooden carved mask sits atop the python skin. The braided hairs, alternating in colors of black and white, symbolize protection and balance in Balinese culture. The snakeskin is a reference to the inner power of kundalini along with the ancestral memories held in the bodies to which these hairs once belonged. They are protected within the shrines Sasmita created. The three embroidered scroll paintings in Act Three (2024), each three meters tall and enriched with elements of nature—plants, trees, and flowers—integrate the botanical wisdom of healing through medicinal plants into the cycle of life. Sasmita collaborates with women artisans in the west of Bali to create her embroideries, incorporating their ancestral wisdom of color into her work.11 She also works with craftsmen in the east for the creation of the canvases, which require intense sunlight to fully dry after being dipped in rice porridge to achieve the right texture and color unique to Kamasan canvases.12

Installation view of Into Eternal Land. First image: Act Two and Three. Second image: detail, Act Two, 2024. Barbican. Photos by Elif Carrier.

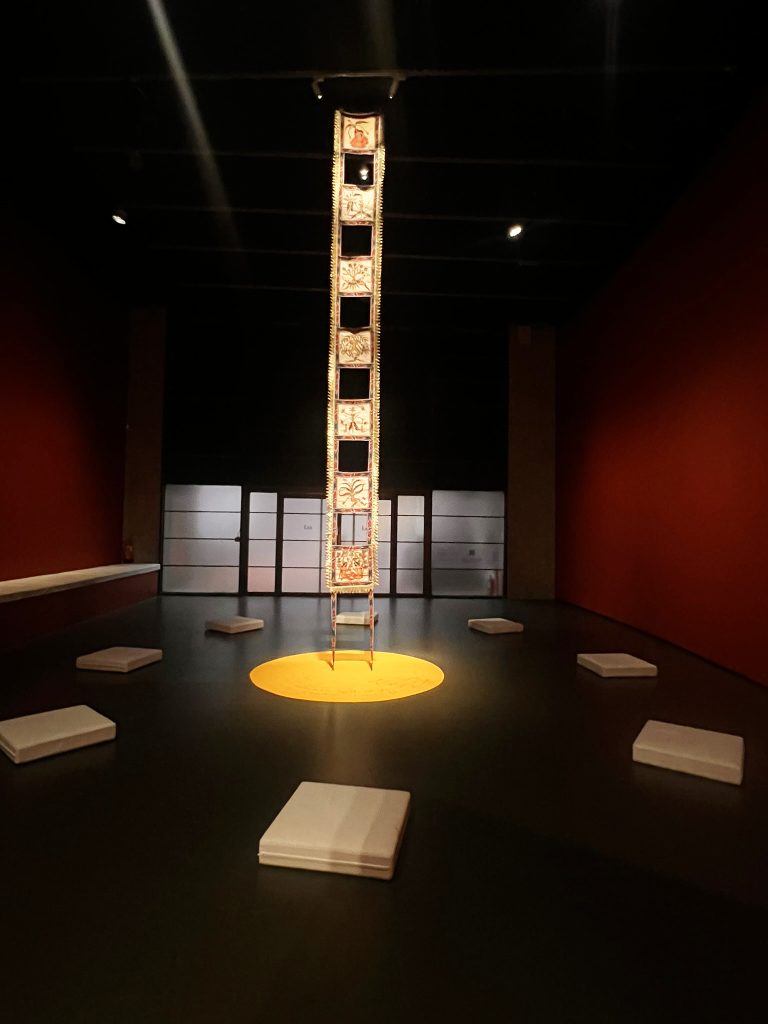

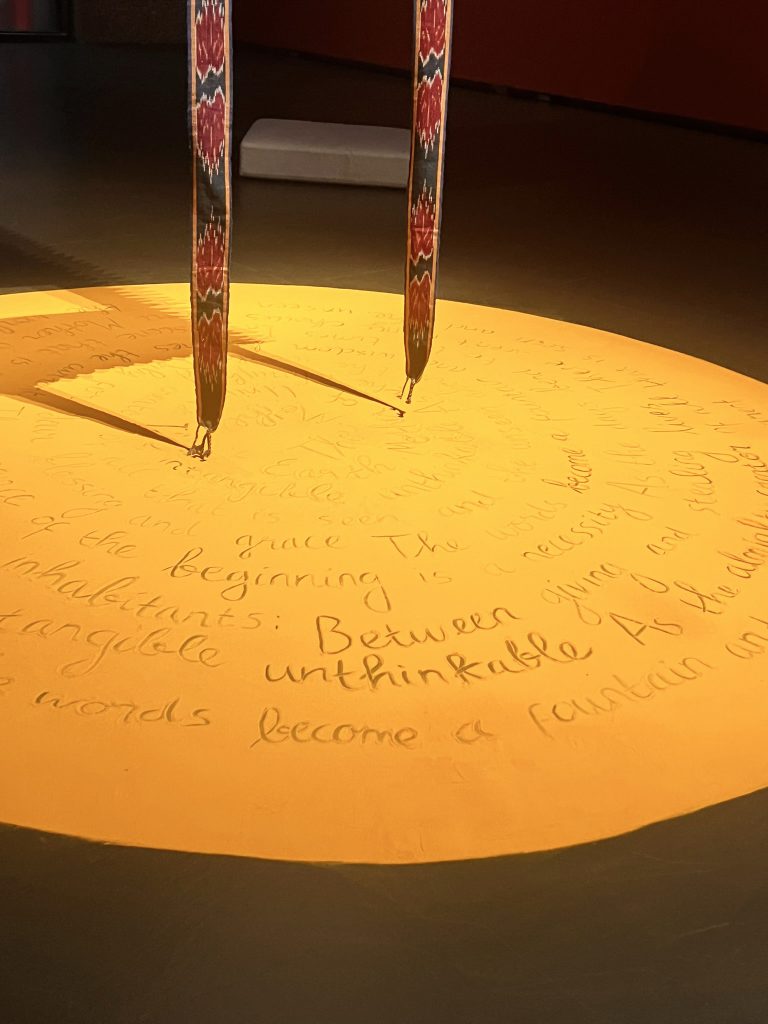

The sound of Agha Pradiya Yogaswara’s music, carrying a quiet, peaceful rhythm, guided the visitors throughout the exhibition and led to the final act, titled Epilogue (2024). Visitors were invited to sit on cushions and meditate in a circle around the final Kamasan painting, which was framed with luminous gold-coloured ribbons shaped into ruffles along its edges, as if belonging to a temple. On the floor were verses of a 14th-century Balinese poem, written in turmeric like a mandala, tightly curved around the installation. Each visitor was given a copy to ponder upon. The verses connect to Mother Earth as the almighty creator, asking for blessing and grace, with joy and acceptance in what is to be found within each cycle of life.

Installation view of Into Eternal Land. Act Three, 2024. Barbican. Photos by Elif Carrier.

Sasmita says that “every artwork holds a possibility of Taksu,” an energetic and spiritual force in Balinese culture—one that is not merely symbolic, but active and capable of effecting change in the world and in one’s experience.

I have been captivated by Sasmita’s work from the very first moment I encountered it. I stood in front of her artworks, gazing into the faces of her women within a space of ambiguity. How could they appear in tranquility while their bodies are in a state of warriorship—their hands gripping swords, their torsos brutally splitting in two? I could not fully explain this visceral tension. What I was certain of, though, was the essence of joy I saw on the faces of the women gazing back at me. There was a quiet sureness in their expressions—not a confidence rooted in domination, but one that draws its strength from the embodied revelations inherited over generations. Sasmita says that “every artwork holds a possibility of Taksu,”13 an energetic and spiritual force in Balinese culture—one that is not merely symbolic, but active and capable of effecting change in the world and in one’s experience. She channels her feminist vision into this energy as a form of resistance. Indeed, there is a palpable sense of urgency within her works— an immediacy rooted in the conditions of our present time. Her situated cosmology and iconography open space for new memories: ones where women are the protagonists and ones that envision Bali free from the aesthetic norms shaped by the colonial gaze, commercialization and exoticism.

Installation view of Epilogue, 2024. Barbican. Photos by Elif Carrier

- Citra Sasmita, “Timur Merah Project: A Pilgrimage of Narrative Memory and Historical Legacy,” published in Citra Sasmita’s personal website. February 12, 2025. Accessed April 18, 2025, https://citrasasmita.com/timur-merah-project-a-pilgrimage-of-narrative-memory-and-historical-legacy/ ↩︎

- Sasmita writes that between the 17th and 19th centuries, around 2,000 Balinese were shipped annually to Batavia (the capital of the Dutch East Indies, now Jakarta), South Africa, and beyond. Women were especially sought after for their beauty, musical skills, and medicinal knowledge. She adds that the most vulnerable were widows, orphans, and women from the lower castes. ↩︎

- Balinese formations and their kings took their own lives in mass suicide as a symbol for resistance to foreign aggression of the Dutch who fought the Balinese with uneven power of canons and guns—resulting with a humiliating victory for the Dutch. ↩︎

- Ibid, Sasmita Essay. ↩︎

- This stereotyping of Balinese women continues to be transmitted through postcards, photographs, and films. ↩︎

- More information on Muriati’s practice can be found in this link: Florek Stan. “Mangku Muriati: Balinese Artist and Priestess.” Australian Museum. June 15, 2021. Accessed on May 3, 2025, https://australian.museum/learn/cultures/international-collection/balinese/mangku-muriati/. ↩︎

- Ibid, Sasmita Essay ↩︎

- Y-Jean Mun-Delsalle. “Citra Sasmita Rewrites Balinese Mythology Through a Feminist Lens.” ARTnews, March 27, 2025. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/citra-sasmita-profile-barbican-1234736914/. Accessed on April 12, 2025. ↩︎

- ISA Art Gallery. Catalogue Essay: Dolorosa Sinaga, https://www.isaartanddesign.com/usr/library/documents/main/artists/187/isa-art-and-design-dolorosa-sinaga-.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2024. ↩︎

- Question as depicted by Sasmita in her essay ↩︎

- Barbican Centre, Citra Sasmita: Into Eternal Land, YouTube video, 5:21, March 20, 2024, https://youtu.be/23unf0F_vu0. ↩︎

- Adeline Chia, “Citra Sasmita: Season of the Snake,” ArtReview, November 9, 2024, accessed on April 3, 2023, https://artreview.com/citra-sasmita-season-of-the-snake/. ↩︎

- Barbican Centre, Citra Sasmita: Into Eternal Land, YouTube video, 5:21, March 20, 2024, https://youtu.be/23unf0F_vu0. ↩︎