In the Studio with Manolya Çelikler

I am standing in front of a new series of works by Manolya Çelikler at her studio on the Anatolian side of Istanbul. “I made the best of this summer,” she says. Her voice is calm. She speaks with clarity and determination. She does not take for granted the time she now has to be in her studio. During the pandemic, she became a mother, and not long after, she decided to dedicate her time solely to her daughter, ending her collaboration with PG Art Gallery, a prominent contemporary art gallery in Türkiye. She retreated into her private life until late 2023. “It was not how I imagined it,” she tells me, referring both to her artistic practice and to her early years of motherhood. But, given the circumstances, she said she did not hesitate. Collectors, gallerists, and curators such as myself continued to visit her. Manolya’s works have that impact. One builds a connection from the heart and carries it forward into the future. The “now” is never lost and the connection is never broken.

“Were you really able to stop Manolya?” I ask. She laughs. Then she explains how she had to learn to stop by giving herself permission to get lost and allow herself to feel powerless. It was a process in which Manolya had to acknowledge her own achievements and prolific artistic production over the last decade without any longer needing to carry “the invisible power medallion.” “The urge to feel safe is very prominent if you are a woman in Türkiye,” she explains and “self-blaming is our ancestral sport in a society where women are continuously criticized.” The political and cultural structures allow and promote such pressures as a means of control over women in daily life where everyone has a right to say anything to a woman.

Within this ordeal, Manolya realized that she was continuing to live and produce in the way society expected of her. She finished university, started working, got married, and had a child – checking off all the expected milestones. Having her daughter, however, was a turning point in her life, one in which she had to deeply examine the meaning of efficiency and redefine it. “One of the most important qualities I learned from my daughter is the practice of staying in the moment,” she says. “This means that some days I can open a book and simply contemplate, without thinking about what I want to finalize in my studio.”

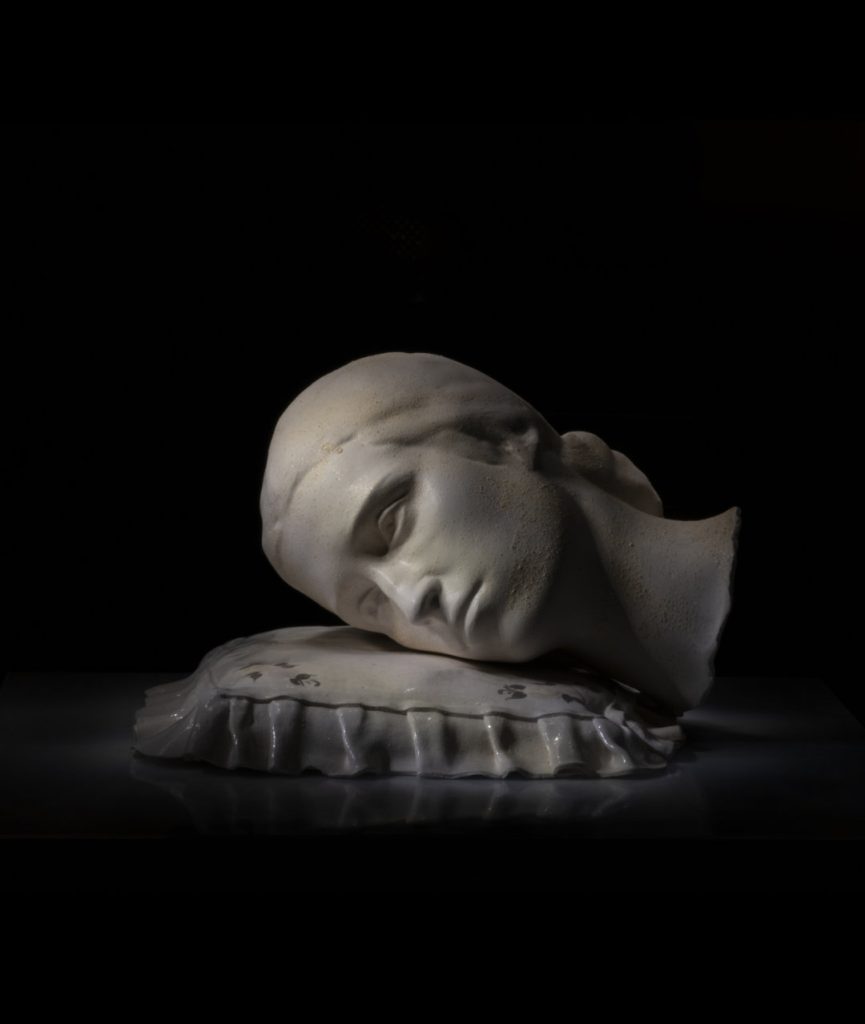

My Own Garden II (2023), made of ceramic, embodies the self-reflection and redefinition Manolya has experienced through its intricate composition of vibrant, lush green leaves emerging from a surface covered in wet lichens and mosses, scattered with remnants of the forest. The green leaves rise from the damp foliage with the audacious force of nature. “In my journey to exist, I spent a lot of time in nature with my daughter,” explains Manolya, reflecting on the early moments when her daughter first attempted to stand, walk, or step on grass. These experiences allowed Manolya to nurture herself as well as to discover what is emerging within her. The interconnection with elements of nature that are present in the My Own Garden series is also carried into the series of ceramic works of women’s heads. In I Remember (2024), the growing moss represents nature’s power of resurgence and resistance.

The act of retreating from the world to “disappear” into sleep, followed by reentering the cycle of daily life serves as a metaphor for the delicate complexities of existence.

The prominent sensation in the series of women heads is owed to the juxtaposition of hiding and revealing. The act of retreating from the world to “disappear” into sleep, followed by reentering the cycle of daily life serves as a metaphor for the delicate complexities of existence. This duality is further amplified through symbolic forms. A pillow bears the profound weight of existence, while the mind remains in constant contemplation. Fabrics moving toward the body symbolize the desire to cover oneself and escape from the world. The flower motifs, a recurring theme in Manolya’s work, reflect the longing for renewal.

Manolya has the gift of discernment from an early age. Born in 1986 in Istanbul, she grew up surrounded by fabrics, sewing machines, and handcrafters of textile. She remembers transforming fabrics into her own creations in primary school, taking references from the women in her own family. As a child, she grew up in her deep introspection reflecting on and harvesting her own observations through writing and reading. Despite her family’s wish to keep art only as a hobby, Manolya knew she wanted to be an artist and it was clear in her head that she would study art. Over time, her family has supported her, convinced by both her determination and by the quality of her work. She received a full scholarship to attend Maltepe University and studied painting, sculpture and ceramics.

Early in her studies, she realized that school alone would not be enough to attain her goals. Although she had talent and the school provided her with the techniques, what she wanted to create was “another” and she knew she had to pursue it on her own. Manolya says that discovering the works of female artists Gözde Ilkin and Canan was transformative. Experiencing their work made her realize the potential of art and opened her eyes to new perspectives within her practice. She reflected on her own past and her relationship with fabric, questioning her choice of materials and the reasons for those choices. She started collecting old handkerchiefs, fabrics, photographs, found objects adding her memories and reflections to them, and bringing them back to life through sewing, embroidery and drawing.

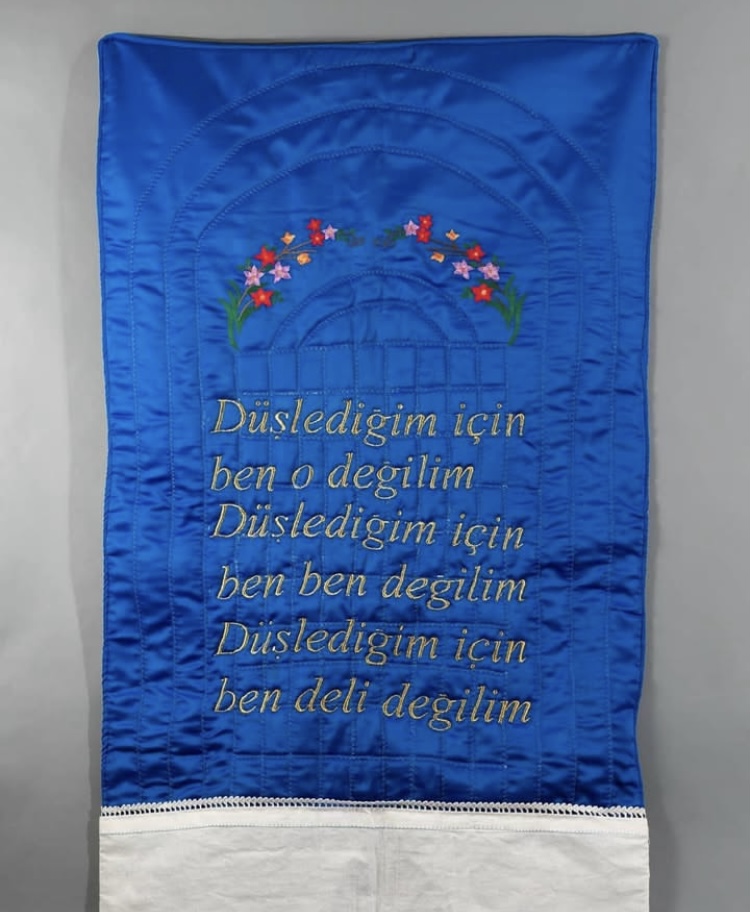

Translation

Because I dream

I am not him

Because I dream

I am not me

Because I dream

I am not insane

One of Manolya’s early series after graduation is Word Flies, Writing in Two Universes (2014). The series consists of quotes from bureaucrats, with the initials of their full names embroidered beneath each quote on the canvas hoops. This mirrors the practice in news reports about violence against women, where only the initials of women’s names are used in television and newspapers. Embroidery and sewing are traditional handcrafts practiced by women to pass time, work on their dowries, or cope with pain. Manolya embarked on the concept of pain. While sewing brings things together, when stitches are undone, a trace remains. In Turkish, the unstitched thread is called çile, meaning “suffering” in English. Each canvas hoop features a hanging thread, symbolizing that although things can be restitched, they can never return to their original state. A trace always remains, much like these statements that leave a lasting mark.

There is an unbroken line of continuity in Manolya’s works, both in her thematic exploration and in her methodology of selecting materials where chance plays no role. The materials she uses are those that have passed through her life. She forms a connection with these materials and carefully considers how to incorporate them into her practice. Her integration of ceramics began in a similar way when she started designing patterns at a ceramic factory, working on the mass production of porcelain items such as door handles and bathroom products. Immersed in the process of drawing the same patterns thousands of times during the day, she began exploring the potential of combining ceramics into her artistic practice during the night.

In Turkish, the unstitched thread is called çile, meaning "suffering" in English. Each canvas hoop features a hanging thread, symbolizing that although things can be restitched, they can never return to their original state. A trace always remains, much like these statements that leave a lasting mark.

The Ah Series (2017), was created during this time and consists of 40 door placards adorned with flower motifs, similar to those Manolya drew while working in the ceramic factory. Each ceramic placard features the Turkish sound “ah” written by hand. “Ah” sound expresses emotions such as pain, longing, or regret but it can also convey love or admiration, depending on the tone in which it is spoken. The number 40 holds significance in Turkish culture, symbolizing both the process of coming to terms with pain and grief, as well as happiness. Newborn babies are kept home for 40 days for protection, and people traditionally mourn for 40 days after the death of a loved one.

Manolya Çelikler. “Moral Compass” (2019). Courtesy of the artist.

Manolya’s use of text, words and sounds such as “ah” is deeply personal and collectively significant for a nation that has been experiencing an increasingly authoritarian political environment. Türkiye ranks first among OECD countries with a 32% rate of violence against women, with one in three women experiencing violence in their lifetime . This thematic exploration is also evident in her Broken Plates series. Each ceramic plate in this body of work is adorned with a flower motif and inscribed with a handwritten word such as “justice,” “moral compass,” or “equality.” The plate is then broken by a male hand and reassembled by Manolya, with visible fractures remaining. The words inscribed on the plates symbolize the collective needs of a nation in times of societal disintegration, polarization, and political upheaval. However, “these words, once powerful expressions, are now only empty statements,” says Manolya, “stripped of their original meaning.”

Although Manolya’s work focuses on her profound inquiries into pain, otherness, oppression, injustice, and the lack of a sense of safety–both as a woman and as a human being in her particular context–there is, in contrast, a deep trust and harmony present in her artistic collaborations.

Manolya Çelikler. “Dear (Respectful) Madam”(2015)

Although Manolya’s work focuses on her profound inquiries into pain, otherness, oppression, injustice, and the lack of a sense of safety–both as a woman and as a human being in her particular context–there is, in contrast, a deep trust and harmony present in her artistic collaborations. This is evident from her early years, beginning with the close relationships she built with her teachers, collectors, her former gallerist, and other art professionals. There has always been a special bond with each of these individuals. She has the ability to trust and speak from the heart, as well as an inner compass that maintains considerate boundaries.

Her creative process unfolds through the same inner compass. She begins with a single element, a sensation, or an influence that moves her. As she works, she steps back and considers how adding or removing certain elements will impact the meaning of the piece. Her process is fluid, with the act of creation being her focus rather than the pursuit of productivity.

Manolya was recently selected to participate in the exhibition series of Olimpos Academy under the mentorship of distinguished Turkish artist, Taner Ceylan. The Olimpos Exhibition Series is an artistic initiative by Taner Ceylan, aimed at enriching artists’ skills through mentoring, exhibitions, and publications. Meanwhile, Manolya is pleased to continue her practice independently from her studio.

Elif Carrier

Elif Carrier is a researcher, curator, writer, and art consultant. Her work focuses on facilitating artistic productions that challenge the historical trajectory and how we act in the contemporary world, in line with her interest in the use of art within society to respond to current urgencies from decentralized positions. She holds a MAS in Curating from Zurich University of Arts and is a Ph.D. candidate in Practice in Curating at Reading University